Mark Bloomfield: Man on a Mission

Mark Bloomfield had two main goals in his life: to seed the Urantia Book on all the continents of the world and to serve humanity by helping those who help the poorest of the poor

by Saskia Raevouri (2019)

Dedicated to Mark Bloomfield (1964-2019) and Sue Tennant (1945-2018), both humanitarians extraordinaire

I FIRST HEARD OF MARK BLOOMFIELD when I published an article in the 2000 Circular called “Sowing Seeds in India,” by a reader named Bhagavan Buritz. Bhagavan told of his experience working at Urantia Foundation’s booth at the 1999 Book Fair in Delhi, India, together with an Englishman named Mark Bloomfield.

That year Mark had been appointed a Urantia Foundation representative, with the mission of placing the revelation in libraries, universities and other centers of learning throughout the world. During the next several years he traveled with the book to India, South Korea, China, Burma, Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Argentina, Guatemala, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, South Africa, and many other parts of the world.

* * *

I first met Mark in person at the UIA conference in Paris in 2002. We struck up a rapport after I mentioned the article and asked him some questions about India. As I am Dutch, and he half Dutch-half English, he asked me to introduce him to a friend of mine, a pretty Dutch reader at the conference in whom he was interested. As I got to know him better he told me about the schools in India he was supporting. I was intrigued with his story of helping an Indian nun in one of the most undeveloped regions of India realize her dream of free schools for underprivileged “untouchables.”

In the winter of 2005-06 I attended a Urantia event at the home of reader Gard Jameson in Las Vegas. There my Canadian friend Sue Tennant showed a slide film about Mark’s Indian schools. In the past two years, Sue had been financially supporting the project and had established a charity, FreeSchools World Literacy, to secure funding. From one school there were now more than twenty. I loved the idea of the schools and began supporting them with a token $25 monthly donation.

In March of 2006, Mark spent two weeks with Sue and her husband Derek at their retreat center, Silver Springs, in Ontario, Canada, where they hatched a plan—with support of Sue's charity—to expand the schools to the north of Thailand, under Mark's supervision.

Sometime after that, Sue suggested that I accompany her—Dutch treat, of course—on a visit to both sets of schools as a second pair of eyes to help evaluate how the donated funds were being spent. Mark would be our guide. By then he was already settled in the north of Thailand, in a town called Fang, where he had established a new group of free schools. We would first visit the Thai schools, then fly to Delhi and Bihar to meet Sister Crescence and tour the Indian schools, staying in the convents. As a world traveler with some spare time on my hands, I immediately agreed, thinking it would be a fascinating vacation if nothing else. Little did I know that it would change my life and give it a whole new meaning and purpose.

* * *

Mark was born to privilege in Stratford-on-Avon but left family and England at seventeen to travel the world.

It was in the mid-1990s, when working with Mother Teresa in Calcutta, that Mark first met Sister Crescence of the Sacred Heart Sisters who have been working to help the poor in Bihar—one of the most populated and undeveloped parts of India—since the 1920s. Mark had organized temporary “eye camps” where volunteer doctors performed corneal surgery for the poor. Sister Crescence, whose eyesight was very bad, was one of the patients.

At that time, Sister Crescence was Superior at St. Mary’s, the Sacred Heart convent in the town of Motihari. There thousands of villages were cut off from civilization, the inhabitants were illiterate, living in grass shacks with no electricity, no toilets, poor health conditions, no medicine, and no hope of rising out of their situation.

The Sacred Heart Sisters had established convents in most of the larger towns in Bihar—Patna, Muzzafarpur, Motihari, Sugauli and Bettiah—providing medical aid through their dispensaries and education through their formal schools. But some families were so poor that they could not afford the $3 per month tuition, and others were so ignorant that they saw no reason to send children to school who could help to bring in an income or take care of their younger siblings while their parents labored in the fields.

Sister Crescence told Mark of her dream of establishing a free evening school, using an empty classroom after hours, to teach the basics to those “untouchable” children, even for a few hours a day. She invited Mark to visit the Motihari convent, never expecting him to take her up on it. In that dangerous and uncivilized part of the world Westerners are rarely seen, as unaccompanied travel is risky and there are no suitable tourist accommodations. The forgotten Sisters of Bihar had not had a visitor for years. But Sister Crescence did not know Mark Bloomfield! Within a few weeks there he was, standing on the doorstep of the convent in Motihari, armed with funds for her to start her first school! And that was the beginning of a new chapter in the lives of not only Sister Crescence but many others as well, myself included! [Read Mark's own story here.]

* * *

For three years, both financial and moral support came from Mark and his family in England. In 2000, Australian Dr. Robert Coenraads also became involved after visiting the school with Mark. [Read Dr. Coenraads' story, My First Visit to Bihar.] Their joint help ensured the development of two schools and a very successful “school-on-a-shoestring” model.

In the meantime, Sister Crescence had been transferred from Motihari to the convent in Bettiah, where she was now Superior. A little goes a long way in India, and with the steady funding she soon had several more non-formal schools functioning in Bettiah and neighboring villages—wherever the sisters could get an “in.” Some villages were so primitive and the inhabitants so superstitious that the sisters had no way of making a connection. In the past it was mainly through their medical services that the sisters were able to penetrate the villages. Because they made no attempt to convert these Hindus to Catholicism but simply wanted to teach them how to improve their lives, they were trusted and welcomed in the growing number of villages where they had made inroads.

In 2005, Mark’s Australian friend, Kathleen Swadling, introduced him to Sue Tennant, who was inspired by Mark’s story to form FreeSchools World Literacy, a Canadian charity with a board of directors and the mission of supporting and sustaining the work. Together Mark and Sue came up with the idea of replicating the FreeSchools model in the north of Thailand for Burmese refugees and hill tribes who would otherwise remain illiterate. With Sue’s support, in 2005 Mark moved to Fang, near Chiang Mai, and began establishing schools. With no Sister Crescence to bring together pupils and teachers and classrooms, Mark found a way to work with existing school authorities, and by 2006 a score of fledgling Thai schools were beginning to function.

* * *

DIARY OF OUR TRIP TO THAILAND AND INDIA

Sunday, October 29

I flew from Amsterdam to Bangkok and checked into the Airport Hotel. Sue was flying in from Toronto via New York and Tokyo. Our plan was to meet at the hotel and spend a night and day there to get over our jet lag before embarking on our mission. I had a feeling things might go wrong when a mutual friend in New York emailed me that Sue’s Tokyo flight was delayed and the hotel could not find our reservation although I had a confirmation number.

Monday, October 30

I slept from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. and not a word from Sue—no email, no phone call. When Mark Bloomfield arrived at four to meet us as planned, I had him come up to the room and sit by the phone while I took a shower. After that we went down to the dining room and planted ourselves within view of the entrance in case Sue should walk in. I had been alerting the front desk all along to be sure and put her in the same room with me if and when she arrived. It was all very strange. What could have happened? It is hard to imagine how frustrating it was in those pre-smart-phone days when you couldn’t get in touch with someone!

Just as Mark and I were on our third glass of wine, Sue appeared at our table. She had been at the hotel since four but was told that I had checked out! Sue insisted that I had to be there, and after much confusion they discovered that I was indeed still registered. Sue then went looking throughout the hotel and finally found us in the dining room, where she joined us for a memorable meal to commemorate the beginning of our adventure. All’s well that ends well!

* * *

Tuesday, October 31

The following morning Mark, who had overnighted with friends in the city, met us at the airport for our brief flight north to Chiang Mai. There we picked up a four-wheel-drive SUV that Sue had arranged for the 3-hour trip to Fang, near the Burmese border. We were going to need such a vehicle to traverse the steep and bumpy, washed-out roads between schools. All the FreeSchools Mark had established were in this area.

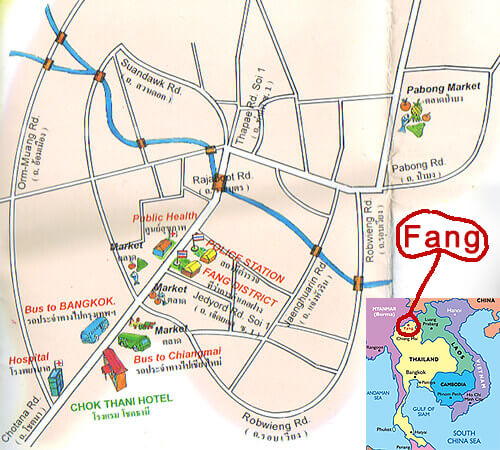

After checking us in to the one hotel in Fang—the Chok-Thani, $12 per night—Mark gave us a quick run around the town then left on his scooter, arranging to meet us the next morning. Like typical tourists, Sue and I walked around Fang taking in the street scenes, shops, temples, and restaurants, where we ate mounds of delicious Thai food at rock-bottom prices.

It was open market in Fang that evening and the street outside was a hub of festivity with music, dancing, hill tribe women in costume, and hundreds of vendors selling wares. We had hour-long leg massages for one dollar then ate rice and noodles and shared a bottle of wine at a sidewalk restaurant. We were off to a fun start!

Some scenes in Fang

Wednesday, November 1

The next morning Mark picked us up for a tour of the surrounding area, including the village of MoungChoum where he was renting a very primitive house. He certainly knew how to live with less than the basics and seemed proud of it!

After that we were off on what would be a three-day round of visiting all the schools. Mark had established three types of FreeSchools: 1) those using existent classrooms and teachers in liaison with the Thai government schools, an arrangement where FreeSchools subsidized the teachers’ pay, which classes were held in the daytime; 2) those conducted for Burmese refugees whose children were not legally permitted to attend official schools; and 3) those in hill tribe villages where most children do not routinely attend school. The last two types were held in the evenings when teachers were available to work extra hours, their salaries being paid by FreeSchools.

In this part of Thailand orange farming is a big industry, and most of the hills are covered with orange groves. The labor is mainly done by Burmese refugees, and the schools for their children were conducted in late afternoon or evening, in open-air shelters.

First on our agenda were three daytime schools, where we met Mark’s liaisons with the government schools: Somdeau, an official, and Pui, a teacher.

After a lunch break at Mark’s favorite restaurant—which ended up becoming our top pick as well—he dropped us off for another afternoon of exploring Fang.

Later that evening Sue went alone with Mark to visit the evening schools and some private “business” talks. When she returned we had another great Thai meal in the town and returned to our rooms, where we stayed up half the night talking about Urantia and FreeSchools. Sue and I never ran out of things to say on those subjects—and many more!

Some schools

Thursday, November 2

For breakfast Mark took us to Bird’s Bar, another haunt of his. There we ran into a Dutch friend of his who was married to a Thai woman. He was taking a group of 15 Dutch trekkers into the mountains, all of whom were eating together at the next table.

After visiting a couple of schools, it was discovered that the bridge was out on the way to the next one, so instead we took a pleasant drive through the countryside before heading back into Fang for lunch.

In the evening we visited four more schools. At one the children had made desks and chairs with empty orange crates, which they carried into class themselves. The parents, most of them illiterate, often waited outside for their children and sometimes sat in on the class to learn to read and write as well.

In the evening we had dinner with Pui and Somdeau.

Friday, November 3

Back to Bird’s Bar for breakfast where the same Dutch group were gathered again. Now that we were meeting for the second time, we greeted each other like long-lost old acquaintances. Mark’s friend joined us at our table and told us many interesting tales of his Thai adventures.

After another round of schools, lunch, and more Fang sightseeing which included a parade through town, Sue decided to stay in and pack as we were leaving the next day. Mark picked me up and we took a spectacular sunset drive to visit the last two evening schools.

Some local scenery around Fang

Saturday, November 4

Over breakfast we recapped our Fang adventure with Mark. After checking out of the hotel we took the three-hour drive to Chiang Mai, where we dropped off the SUV and had lunch together before flying back to Bangkok.

Having been to Bangkok several times when working in Asia in the early 1990s, I introduced Sue to my favorite hotel, the Royal, near the tourist area of Banglampu, which I knew quite well. While Mark took off to visit his old haunts in the neighborhood, Sue and I walked around the corner for a big steak dinner and bottle of wine at the Sky High restaurant. It was a hot and humid evening, and we sat outdoors with many other diners.

Sunday, November 5

Mark met us at the Royal Hotel for the big breakfast buffet, and after checking out we took a taxi to the airport for the flight to Delhi, where we planned to spend one night at the Mohan, a hotel I had booked for us on the internet, before flying to Patna the next day. Mark, an expert on Delhi, thought little of my choice of hotel, but the room service and the food were great, so for one night he put up with it!

Monday, November 6

We were up at 4 am and off to the airport for our 8 am flight to Patna, only to discover that the flight was delayed until 10 am. We learned one thing about Mark: if we were supposed to be at the airport three hours ahead, he wanted to be there four hours ahead—just in case! The ironic thing was that every flight we took together was inevitably delayed. The good thing is that it gave us many more hours to communicate with each other—about the Urantia Book, the FreeSchools, and our lives in general.

Mark entertained us with tales of his extraordinary adventures all around the globe. I wish I had made notes as I can't recall them well enough to describe them here, but he was a true daredevil and survived many close calls.

Having made this trip to Bihar many times, Mark knew all the landmarks from the plane window, pointing out the Himalayas and giving us the historical background the city of Ranchi, were our plane stopped to drop off and pick up more passengers.

We were met at the Patna airport by Sister Crescence and three other sisters, in a sturdy-looking Mahindra jeep. Mark explained that this car was built in India especially for Indian roads, and it didn’t take long to figure out why. Our drive to the Muzzafarpur Sacred Heart convent to spend our first night, a distance of 72 kilometers, took us over potholed, crowded and polluted roads, dodging cows, pedestrians, motorcycles, rickshaws and overloaded buses at every bend. Our driver seemed to take it all in stride, beeping the horn non-stop as he wove in and out of obstacles along the way, on a ride that took us well over three hours. If we thought the Thai roads were bad, these were far worse!

Along the way we were forced to take a detour through a village, where we stopped and got out of the car. The local women all came out to meet us, and were delighted when we gave them our unopened containers of airplane food. To Sue and me these women seemed poor, but in retrospect, compared to what we were about to experience, they must have been quite well off! The scene was so colorful we had to take pictures!

It was dark when we arrived at the Muzzafarpur convent, where we were lovingly welcomed by several Sisters with a simple meal of chicken, potatoes, and vegetables in the communal dining room. The original plan was for us to visit the three FreeSchools there that used after-hours classrooms, but we arrived so late due to our delayed flight that the children had been sent home. Instead, three little boys who were boarding at the convent were brought out to meet us and presented us with garlands.

After dinner, Sue and I were immediately shown to a bare room with minimal toilet facilities and basic furnishings. For us this was roughing it, but little did we know then how luxurious our accommodations were compared to how others were living, including the sisters themselves! Our wooden-plank beds without mattresses were covered in a heavy cloth, and thankfully equipped with mosquito nets. We thought we’d be awake all night, but we slept like logs. The convent felt like a peaceful sanctuary after our harrowing drive from Patna.

The drive to Muzzafarpur

Tuesday, November 7

The next morning, we woke up early to the pleasant sound of the sisters singing hymns nearby in the convent. We learned that they do this every morning, before anything else. Our breakfast was ready and tailored to our Western needs: fried eggs, toast, jam, butter, little packets of processed cheese, and very sweet tea and coffee—all provided especially for us as the sisters subsist on much simpler fare.

Still dusty from the day before, we were off to Motihari to see the first round of FreeSchools, promising the Muzzafarpur sisters we would return to visit them on our way back. As we were leaving, the pupils attending the formal school came out to meet us and we took pictures. Students paid $3 a month each plus books and uniform, totaling roughly $65 per year—an exorbitant amount for most families in Bihar. Each convent has these schools, which is their chief means of income. The Sacred Heart order is self-supporting and receives little or nothing from the Catholic Church.

The 84 km drive from Muzzarfarpur to Motihari was a continuation of the same rundown road of the day before. In the daylight we could see small villages along the way, mostly comprised of grass huts with no modern conveniences, with women squatted on the ground and small children running free. In Motihari, at St. Mary’s convent we were once again welcomed by a group of sisters who had very sweet, milky coffee and biscuits ready for us.

After that it was time to visit the FreeSchools, in the town where it all began almost ten years earlier. As we pulled out of the driveway, Mark pointed out a giant dollar sign at the entrance of the convent, just across the way. He said this symbol meant something different here, and that these sisters would be mortified to learn that it stood for something so unGodly as a form of currency! I’m certain they were not so ignorant, but they must have had something else in mind when it was agreed to place that sign there!

The first school was in a fishing village made up of grass shacks, where classes were held under a large tree. My first sight of these kids sitting on the ground in rows in their fanciest dresses and cleanest shirts—so eager to learn and so excited to see us—was very emotional. Sue and I looked at each other and we were both fighting back tears. Sister Crescence told us these kids had never seen people like us before. We stared at them and they stared at us—especially at Mark who towered over all of us like a fair-skinned God from another world.

After a song of welcome by the older girls, they approached us to place garlands of marigolds around our necks. Sister Crescence then quizzed the kids verbally on their skills in Hindi and math, and each time enthusiastic hands shot in the air with the answer. She then invited Mark to say a few words, which she translated. For the first of many such addresses, Mark gave a dramatic pep-talk admonishing the students to always listen to the teacher. Sue and I were also asked to say a few words of encouragement, and whatever we said Sister Crescence translated it into words that received a hearty round of cheer. Before we left, Sister Crescence dug into the shoulder purse she always carried with her, and pulled out a bag of boiled sweets which she gave the teacher to distribute among the kids. Their eyes lit up in anticipation of this rare treat!

After this adventure and lots of picture-taking on the walk back to the jeep—where we were followed by half the village—we were off to the second school. In this village an inhabitant had donated his building for FreeSchools use. We followed the same pattern—a welcome song by the older girls followed by garlands of marigolds, a quiz by Sister Crescence, Mark's rousing pep-talk, and a few words from Sue and me. There was no shortage of spectators, and Sister Crescence would use this opportunity to plead with the parents on the sidelines to allow their children to attend the schools.

After that we visited two more schools, one of which was held outside in a yard where cows were lying around and where the older girls were taught sewing using treadle machines.

By now we had learned to remove the previous garlands to make way for the new, and after a few visits our jeep was littered with piles and piles of fresh strung flowers. At every school, we noticed, no sooner had a garland been placed around Sister Crescence’s neck than she quickly removed it. We soon found out why: These beautiful flowers left orange and magenta stains on our clothes, and she had to conserve her habit! Seeing that Sister Crescence’s habit was held together with safety pins, I asked her how often she received a new one. With a wave of her hand she replied, “Oh, I just wait until an older sister dies and then I take over her habit.”

After returning to St. Mary's for a hot lunch of chicken, potatoes and vegetables, we were off again to see four more schools. To the first two we went on foot from the convent through the town, causing quite a sensation as we passed by! A young boy led Sister Crescence by the hand, as she is almost blind. By now we were used to the sight of cows and cow dung drying in the sun—a big industry here as it is used for kindling.

In our visits, we had added to our routine. After our welcome, Sister Crescence’s quiz and Mark’s inspiring words, either Sue or I would point to the group of village women and scruffy children gathered around and say, in all innocence, “Sister Crescence, why are these children not in school?” This would give Sister Crescence the opening for launching into a heartfelt speech imploring the parents to enroll their kids in their village FreeSchool. We also took turns asking the kids what they wanted to be when they grew up. The answers were almost the same every time: doctor, teacher, pilot, lawyer, policeman, engineer, superintendent, magistrate, and Sister. Everybody wanted to be something, and nobody wanted to be a rickshaw driver!

The Motihari Schools

Back at St. Mary’s, after tea on the lawn and a question-and-answer session with the Motihari teachers, we took our leave for the 42-km drive to Bettiah, which would serve as our headquarters for the next three nights. It was so hot that, even though the air was thickly polluted, we drove with open windows in the un-airconditioned vehicle. Sue’s contact lenses gave her endless trouble as tiny specs of dust flew in her eyes, forcing her to cover them with her hands as she moaned in distress. Because of this, she missed many of the intriguing sights we passed along the way.

* * *

As we approached the Bettiah convent in the dark, lights went on to reveal a high metal gate and a wall at least ten feet high. The gates were opened to let us through and immediately closed and locked. Mark explained that there was so much crime around here that after nine p.m. guard dogs were let loose to patrol the property and, once inside their quarters, nobody could leave until morning.

We were escorted to a small building consisting of two rooms, each with its own toilet facilities. One room was for Sue and me to share and the other for Mark. As before, the beds were wooden planks covered with a padded sheet, with a small pillow, and draped with mosquito nets. One window had no glass, just bars, letting the mosquitoes in and out. Our washing facilities, which locals would consider a luxury, consisted of a cold-water tap in the wall, a bucket, and a drain in the floor. The toilet was western style complete with toilet seat, and after having squatted over holes in the ground since we arrived in Bihar, this was a pleasant and unexpected surprise. There was no toilet paper, and when I asked Sister Crescence about it, she said, “Oh yes! We still have some from the last visitor,” and returned with a quarter roll of pink paper at least three years old! But we were prepared with our own stash, having heard in advance that this product was not for sale around here. Indians, we knew, have other ways of cleaning up.

Soon after we were settled in, two sisters lovingly brought us each a bucket of warm water, saying, “We knew you would like a bath after your long journey.” To us, this was heaven-sent and we were grateful. Indians take cup after cup of water and pour it over their soaped-up bodies, instead of standing under running water, which is not always available. Later we learned that heating the water—and all cooking in the convent—was done with coal.

After freshening up, Sue, Mark and I met up in the guest dining room where another hot meal of chicken, potatoes, and vegetable of the day awaited us. We were told that this room, which had been added on to the dormitory housing retired sisters, was donated by a European supporter years ago to give guests a private meeting place. Since no visitors ever came, it was now used as the elderly sisters’ dining room. In anticipation of our arrival, however, it had been restored to its original purpose, with a large table in the middle and five or six chairs. At all times the sisters were at our service, with a meal, a snack, tea and instant coffee ready for us.

For two hours a day, between seven and nine in the evening, electricity was available at the convent. At nine the lights went out, so we quickly took turns charging up our camera batteries in the one wall outlet whenever we were in the room. (Next time we would remember to bring a power strip!) This was tricky, and often our cameras ran out of juice mid-afternoon, so we missed many great shots. We were provided with some electrically-charged battery-operated lanterns, but when the overhead fan went out at bedtime in the extreme heat we suffered! There were also mosquitoes galore, so we stayed inside our netting as much as possible.

During our long drives, Sister Crescence lamented that many of the problems they dealt with in their work were caused by alcoholism on the part of the men. Sue and I enjoyed our evening cocktails and had no plans to quit so suddenly. Knowing it would be difficult for us to purchase alcohol in Bihar, and not wanting to travel with bottles of wine, we brought along a liter of vodka from the duty free. This was to last us for the entire time, so we had to ration ourselves carefully—no more than one stiff drink a day each. Mixers were easy to get. Though we had not intended to drink openly, learning how Sister Crescence disapproved, we now had to hide the booze and drink only after the dogs were set free, and make sure to take the empty bottles with us when we left!

The building next door to ours were administration offices for the Fakirana Sisters Society, the organization under which the Bettiah sisters did their work in the field. The office worker, Amrita, had a computer with a dial-up connection and the building had constant electricity, so we were finally able to check our email. This became a treasured routine each evening, when we were briefly able to connect with the outside world, before the lights went out and the dogs were unleashed.

The Sacred Heart convent in Bettiah

Wednesday, November 8

Exhausted after a sleepless night, we were up early for breakfast. Several sisters came by to meet us, some of whom Mark remembered from his earlier visits. Sister Crescence joined us every morning, and during this time we discussed plans for the schools and many other ideas.

On this first morning Sister Crescence lamented that her cross was missing, and the convent had been turned upside down looking for it. Our pictures from the day before showed that she was wearing it, so it must have happened after we returned. Sue immediately offered to go out and buy her another one, but Mark held her back: "That's a wonderful gesture, Sue, but it can't just be any cross. It must be a very special kind, and blessed by the Pope, and who knows what else!" For the rest of our visit, as our photos show, Sr. Crescence was "crossless."

Mark explained that technically these women were not nuns, but sisters. The difference is that nuns live a life of prayerful contemplation, whereas sisters—such as Crescence—take vows of poverty and devote their lives to ministering to the poor and downtrodden, working as teachers, nurses, and in other social service occupations.

The first morning Sister Crescence gave us a tour of the convent grounds. There was the main building which housed the sisters, a large chapel, a dining hall with kitchen and pantry, a hospital with an outpatient clinic, a dispensary, several office buildings for social workers, a dormitory for novices, a large school building for the formal school classes, garages for vehicles, our guest quarters, and several outbuildings some of which housed animals, such as cows and farm animals. The surrounding land contained gardens, mostly herbs and vegetables, and a burial place for former sisters. There seemed to be many workers on the grounds tending the gardens and the animals.

* * *

Immediately afterwards we headed out in the jeep for our first round of four schools. As we bumped along on the pot-holed roads, Mark commented that these particular villages were very close to the border of Nepal.

At each school we were first greeted with serious little faces, the kids not knowing what to make of us. We now added a new routine to our act. As we were leaving, we would wave and call out, “Bye, bye!” and take pictures at the same time. The kids would break into big smiles and shout back, “Bye, bye!” waving and laughing as we walked off. As always, at each school the entire village population came out to observe us and say farewell!

At some schools we were served tea and biscuits, but Sister Crescence would not let us drink the beverages because she said the water had not been properly boiled. She was always on the lookout for us and our delicate Western stomachs! She also made sure the bottled water we drank was purchased in the right shop, as some unscrupulous vendors sold plastic bottles filled with unsafe well or even tap water. Though almost every village had a communal well, Sister Crescence explained that they were very shallow and contained many contaminants. Though most villagers could tolerate this, others suffered from illnesses brought on by unclean water. Teaching them various ways of purifying the water was one of the sisters' objectives in their efforts to bring civilization to Bihar.

At the last school of the morning we arrived so late the teacher and children had been sent home. While someone ran to call them back, we stood around encircled by curious villagers. At every school so far chairs had been provided—everything from kitchen chairs to fold-up garden chairs to stools. Not wanting us to experience even a moment of discomfort, two men rushed to bring us the fanciest chair in the village—a long blue wooden bench, which they carted from several houses away. After proudly setting it down for us, they insisted we sit on it until while waiting for the teacher and pupils to return. Of course, this had to be a photo-op!

This class was conducted in the back yard of a villager who had donated the space. The female teacher was handicapped and arrived limping on bare feet. Mark explained that being disabled was considered a stigma—especially for girls—and the fact that this woman was hired as a teacher elevated her social standing in the village.

* * *

After our meal and before lights out, we were sitting on our porch with Mark rehashing the sights and sounds of the day, certainly one of the most impression-filled days of our lives. Sue was brimming with ideas on how Sister Crescence and her crew could do things better and faster, to which Mark always had one response: "Sue, let them do it their way!"

The Bettiah area FreeSchools

Thursday, November 9

The next day Sue took some time off, and I went alone with Sister Crescence and Mark to visit the schools in the town of Sugauli, about 23 kilometers from Bettiah over the rough roads we were slowly getting used to. First we stopped off for morning coffee at the Sacred Heart convent there run by Sister Ambrose. This convent specializes in all manner of disabled children, some boarders and others living at home with their families but attending school during the day. Before going inside, the sisters brought out a small group of boys in uniforms, mostly polio victims, who were boarding at the convent and attending the formal school. I thought polio had been eradicated in the world, but not here! My heart went to these boys, and I insisted we take a picture so it would remain engraved on my brain—a significant moment for me, when I realized I had to help those who were helping these kids!

Inside, a group of disabled children were gathered in a dark hallway, electricity being a luxury and used sparingly. A precious little girl with a deformed leg was brought forward for me to inspect, and when I made eye contact with her I had another defining moment in my life. I had to help! Sister Ambrose told me that the Lilianefonds in the Netherlands paid for the children’s surgeries, but that they could always use extra funding for their housing and schooling. She explained that these unfortunate children, especially the girls, were treated like outcasts in their own families, it being considered a curse to have a disabled child. The convent was full to capacity with boarders, and Sister Ambrose showed us a room where about twenty boys slept in little cots.

Outside stood a tricycle wheelchair, something we had noticed everywhere we went in Bihar, used by people who can’t walk—at least, those who are lucky enough to afford one! It works like a bicycle but instead of pedaling with their feet they turn a handle with their right hand and steer with the left. They operate in the middle of traffic along with cars, horse and carts, buses, motorcycles, pedestrians, and cows. Sister Ambrose told me the convent only had one that everyone had to share, and they could use 14 more. These could be made locally in Patna for around $100 each and also gave the tricycle maker a chance to earn a few rupees. (When I returned to the States I raised $1,500 for tricycle wheelchairs! Read my article here.)

From there we drove a little distance to visit one of the four FreeSchools in Sugauli. This property, including the building, had been left to the Sacred Heart Sisters in somebody's will and was in a state of disrepair. There was no electricity so the room was dark, but with a roof over their heads to protect the kids from sun and rain, it was a step up from sitting outside. When we emerged from the building, curious throngs of kids were waiting by the entrance. Mark said it was because they’d heard Sister Crescence was handing out sweets!

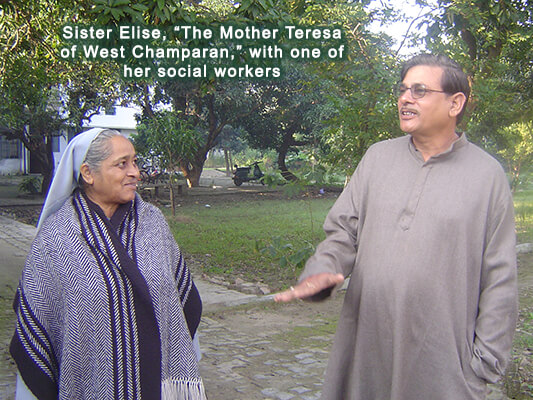

The morning in Sugauli

Back in Bettiah, in the dining room after lunch I had a one-on-one talk with the dynamic Sister Mary Elise. With offices on the convent grounds, Sister Elise supervised a staff of over 150 social workers in the field and was known as “the Mother Teresa of West Champaran," the area that includes Bettiah. She told me the history of the Sacred Heart Sisters and the Fakirana Sisters Society, the name of their official social work organization. In operation since 1957, the Society is made up of Sacred Heart Sisters in Bettiah who focus on improving the lot of villagers in the immediate area. They deal with health and education, child safety, children with disabilities, trafficking, slavery, child marriage, AIDS, and more.

I asked her why the sisters couldn’t get more funding from the government, why they had to rely on non-Indian charities and private people like us. She explained that they refused to pay the bribes, which were sometimes as high as 30%.

I don't remember discussing religion with the sisters, and certainly not the Bible or the Urantia Book. (Mark said that had given them one years ago but it remained unread, stashed away somewhere in the convent, waiting to be discovered by some future truth seeker.) However, we often talked about God and what he wanted from us in this life. When I asked Sister Elise this question, she replied: “God wants us to help others—especially the poor, the underprivileged, the destitute, and those without hope.” With that I could heartily agree! Everything the sisters do is in the name of Jesus, and watching them in action with their good works, in a remote outpost of the world where they receive little recognition, to me they are Jesus come back to life. Having taken vows of poverty, they take nothing for themselves and devote their entire lives to making their part of the world a better place for those less fortunate. Talking about religion seemed pointless, as they were so busy practicing it!

In the afternoon we all walked across the street to visit the three FreeSchools being conducted in the convent’s formal school classrooms after hours.

As Sister Crescence asked her usual test questions, one little boy was so anxious to show us his stuff that he ran up to the blackboard three times, even when Sister Crescence had selected another child! It would be tragic if an enthusiastic boy like this never gets a chance at an education.

One girl was thrilled that she was picked, but when she wrote her answer on the blackboard it was wrong. Another girl came up to correct it, and the first girl went back to her seat in tears! My heart broke for her as she was so eager to make a positive impression on us.

This was followed by the presentation of garlands and a song and dance performance by the older girls. The Bihar kids, we noticed, love to sing, dance and act. Because they have no television and little chance of going to the movies, they create their own entertainment, with homemade costumes and routines worked out between themselves. Though we didn’t understand Hindi, they amused us with their clever pantomime gestures, which Sister Crescence attempted to translate. We were watching future Bollywood stars in the making!

Next we were driven to visit the FreeSchools in another Sacred Heart convent, the VanHoeck convent in the center of Bettiah, deep in the middle of a neighborhood of concrete structures. Here, apart from their formal schools and one FreeSchool, was a room where the older girls were taught typing and sewing.

From there we took the jeep across town to the Bettiah Diocese, to visit the Bishop, Victor Henry Thakur.

Here something happened that took me aback. Mark, in a previous visit, had presented the Bishop with a Urantia Book, which now sat prominently in the middle of his bookcase. As we entered his office, I spotted it and exclaimed, “Hey! The Urantia Book!” Mark looked panic stricken. “Sh-h-h-h!” he hissed, giving me the evil eye and a strong nudge. It seems as though Mark knew the Bishop was not ready for it and it should remain “hidden” until the right person came along, perhaps many decades hence. In any case, I should not attract any attention to it!

Though the Bishop certainly lived the high life compared to the poor Sisters—an impressive dwelling, a fancy vehicle, the latest mobile phone, a splendid wardrobe—he was someone we grew to like a lot during our conversation. Over tea and biscuits in his large kitchen—and an army of mosquitoes which he didn’t seem to notice—he told us how he had worked for unity among the three big religions in the area. He had encouraged the Christians, the Hindus and the Muslims to all respect and celebrate each other’s holidays, and even to wait on each other during those times.

While listening to his story several mosquitoes flew inside my pants leg and I had to leave the room. Sister Crescence followed me to show me the bathroom, and once she had me cornered she managed to tell me about a woman in desperate need of medical help which would cost 8,000 rupees [about $200 in 2006]. I looked in my wallet and that was precisely the amount I had, so I handed it over! (Several months later I received a letter from the sick woman, who happened to be Sr. Crescence's sister-in-law, Margaret, thanking me for saving her from “immature death.” She included a stack of receipts covering surgery, ambulance and medicines—all for under $200!)

After dinner, we starting packing up because the next day, after brief visits to three more Bettiah schools, we were to leave and return to the schools we missed in Muzzafarpur.

The afternoon in Bettiah

Friday, November 10

The next morning two little girls in their best dresses appeared at the convent on foot to fetch us, to guide our driver to their school on the outskirts of Bettiah. As usual, as we entered the village, we were greeted by a welcoming committee of cows, scruffy children, curious men, and silent women sitting around in colorful saris. While these women make a beautiful picture when clustered together, the sad fact is that they are illiterate, and the future of their daughters is equally bleak unless a way is found to help them get an education.

For this school approximately sixty children were assembled on a porch, donated by a villager who, despite a raging fever, came out to meet us.

From there we drove to a nearby village where the class was conducted in a yard, entered through the door of a house. The teacher was very young and also handicapped. After the usual testing and questioning—by now we had perfected our roles—we were offered refreshments, which this time Sister Crescence approved of. I will never forget us drinking tea and eating biscuits with scores of pairs of wide-open little black eyes staring at us in total silence. We fell hopelessly in love with these little faces!

On the outskirts of Bettiah

Back at Sacred Heart, Sister Crescence took us on another tour of the convent grounds, this time with a purpose. She led us to one structure, now fallen into disrepair and housing cows and other animals. Her dream, she told us, was to renovate the building to become a dormitory for poor village girls to live and study at the convent, to prepare them for formal school classes at the Sacred Heart High School. I promised I would help her. [When I returned home I raised the money for the building—which turned out to be a lot more than clearing out the cows, a fresh coat of paint and a new roof—and cut the ribbon at the grand opening in 2010 of an enormous two-story structure! The project was named The Bridge Course Program for Poorest Girls. Read the stories here: The Girls Dormitory Project and 2010 Bihar Revisited.]

Sue, a gourmet chef who had hosted cooking retreats at her magnificent property in Silver Springs, Ontario, was taken aback by the unhealthy, coal-blackened kitchen. The walls were filthy and the equipment outdated. She took this project upon herself and vowed to find help to have it renovated. [Sue was able to secure a grant from the Conrad Hilton Foundation, who have a program for supporting Catholic sisters, and in 2010 the kitchen was fully renewed. The grand opening took place together with the opening of the Bridge Course building.]

As we were strolling along, Sister Crescence decided to take us around to visit the sisters at the adjoining convent, a different order whose formal schools and related work specialized in deaf children. Apparently there are quite a few Catholic orders in Bihar, each working to improve the lot of this uncultured, uncivilized part of the world in their own way.

* * *

That evening back in our room, as we were clandestinely sipping our well-earned cocktail and going over the events of the day, Sue made an astounding suggestion: Why not have the Urantia Book "youth" volunteer to come to Bettiah to revamp the girls' dormitory building and give the kitchen a lick of paint?

"Are you kidding?" I said. "Besides expecting to have their air fare paid and demanding comfortable accommodations, they would never put up with a bucket of water for a shower, mosquitoes day and night, the simple food, and being locked in a room from 9 pm till morning without electricity! Not to mention having to go out and do hard manual labor in the blistering heat! The whole idea is to provide employment for the the locals!"

Sue laughed and agreed that it was a foolish suggestion!

Tour with a purpose and goodbye to Bettiah

After lunch, our bags were loaded onto the jeep and we said our goodbyes to the small group that had come to wave us off. Besides the driver, crammed into the vehicle were the three of us, Sister Crescence, and four Sisters who were going to Patna for medical reasons. First stop was Muzzafarpur, where we were expected to catch the three classes we had missed several days earlier.

The Sisters there welcomed us as old friends, and we felt the same way about them. After a brief reunion over tea and biscuits, we visited the classes, all of which were held within the convent walls in the regular classrooms of the daily formal schools.

Muzzafarpur

Some scenes along the way as we drove from Bettiah to Patna

Soon we were back on the bumpy road, heading to Patna to spend our last night in Bihar at the convent there. This was the main Sacred Heart convent, far grander and better-equipped than the others. The rooms were bare, but with constant electricity and seemingly mosquito-free. We were each escorted to our separate rooms to wash up and prepare for our evening meal.

As I was unpacking my bag I noticed a group of very curious young sisters hovering outside my door, very anxious to meet me. The tiniest one asked if I could take her with me, and when I said sure, if she could fit in my bag, they all broke out in a fit of giggles. While Mark and I were waiting out in the hall for Sue to go to the dining room together, they offered to sing for us. They sounded like angels and would have sung twenty songs if we had let them! These are our future Sister Crescences!

The next day, our last, was spent walking around the grounds, which included a new cathedral under construction. Funds for this type of project come from Catholic donor groups in much the same way that we are raising money for FreeSchools. Later in the morning we met the teacher of the Patna FreeSchool. Because the class was conducted on the convent grounds in an existing classroom which was in session, it was not possible for us to meet the class, so the teacher presented us with a photo instead.

Our last meal was held in the private dining room of the Superior General, together with other key sisters of the convent. For us they had made the usual chicken, potatoes, and vegetables, while they ate curries, dal, chapattis, rice, chutney, and interesting looking spicy dishes though very simply prepared. I said I would love to eat their food instead, but once again they smiled and said I was just being polite. “You wouldn’t like it!” they said. Yes, we would, and next time we will insist!

After taking some pictures with the sisters and saying farewell, we were off to the airport for our flight back to Delhi.

Mark said something perplexing to Sister Crescence as we were parting at the airport: “My job here is done. I have delivered these people to you and they will take care of you. This will be my last visit to Bihar.” Sister Crescence was taken aback. She thought the world of Mark, and many times since then she asked me about him, saying, “Why did he say that? Why doesn’t he want to come back?”

* * *

The convent in Patna

* * *

After our incredible, emotional experience in Bihar, the three of us remained in Delhi together for a few days of reminiscing and brainstorming. Mark knew all the ropes in the exotic budget Paharganj area of Delhi—which hotel was best for us, where to eat, where to shop, where to get cash, where to get internet, how not to get ripped off, and how to behave so as not to shock the Indian people! In Bihar we were under the protection of the sisters, but here in the big city we were on our own and vulnerable.

The first thing Mark did was insist we change hotels from the Mohan which we had booked online, to the Ajanta—a great find and where I have stayed each time since. Mark found the Ajanta too upscale for himself (though a good room with all the facilities was only around $25) and stayed at a rock-bottom place somewhere down the street.

A funny thing happened the evening we arrived and were all sitting around together in one of the rooms of our “unsuitable” hotel. We wanted to buy wine, and Mark suggested we let the hotel “boy” to go out and get it for us as we would certainly be overcharged. The front desk sent up a young man of about 18 in uniform, and wine-connoisseur Sue gave him instructions something like this: “A bottle of red—not sweet but not too dry, perhaps a Merlot, or a Pinot Noir, but not a Cabernet. For the white, we want it very dry—preferably a Sauvignon Blanc, but if not a Chardonnay or even a Pinot Grigio, but absolutely not a Riesling.” We gave him 200 rupees, equivalent of around five dollars at the time. Ten minutes later the boy returned with a bottle of whisky and a bottle of vodka. “That’s not wine!” we said. Pointing first at the whiskey, the boy said, “Red wine,” and then at the vodka, he said, “White wine.” We were amazed that you could buy hard liquor for so little, and proceeded to drink some of it anyway and suffered terribly the next day!

* * *

At that time Sue was an Associate Trustee of Urantia Foundation and had been asked by them to visit ISPCK (Indian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge), a well-established Indian Christian book publisher and distributor. A few years earlier, after meeting UF representatives at a Delhi book fair, ISPCK had agreed to print up the 2097-page Urantia Book for Urantia Foundation at a cost of a few dollars each. Read more about it here. The goal was to seed India with an affordable book in seminaries and bookstores where Christian literature was found. Mark had been involved in overseeing the project. The purpose of Sue's visit was to find out what was happening with those Urantia Books.

Mark had already returned to Thailand, and I accompanied Sue to the ISPCK headquarters in Old Delhi, where we were welcomed as honored guests by Rev. Dr. Amos Ashish and his assistant Ella Sonawane. (Not only did ISPCK publish Christian literature, they also financed their own brand of free schools and women's empowerment centers in some of the poorest sections on the outskirts of Delhi, which in the next few days they took us to.)

Back in Delhi for a few days

After a lavish spread of delicious catered Indian food, Rev. Amos gave us a tour of the ISPCK facilities and led us into a storeroom filled with shelf after shelf of many hundreds of Urantia Books. They were well made, with brown faux-leather covers, gold-embossed lettering, and the look and feel of a thick Bible. Rev. Amos explained his situation: books were being returned from the seminaries, with the message that they could not use the Urantia Book, that it went against all their teachings—the atonement, the Virgin Mary, the miracles, and more. The Foundation had stipulated that the Urantia Book was not to be advertised, which meant it could not be included in the ISPCK catalog which reached all the Christian outlets in India, making it impossible to get it into bookstores. Did we have any ideas about what to do with them?

Here is where Sue came up with a brilliant idea. Mark had talked about going to Africa after his work in Thailand was finished, hoping to find another Sister Crescence to partner with. Why not ship the books to Africa where Mark could place them up and down the continent in institutions of learning to his heart’s content? This suggestion was met with enthusiasm by all, and Sue agreed to present it to the Urantia Foundation Trustees at the next board meeting.

* * *

As soon as I returned home, I wrote a report about my experiences in Bihar, “FreeSchools—A Life-Changing Experience.” Using my story (which is a variation of this article), I raised over $20,000, which I handed over to Sister Crescence when I returned to India with Sue and Dr. John Lange the following year.

Around the same time, Mark was given the go-ahead by Urantia Foundation to seed the Indian books throughout Africa. In March 2007 he left the Thai operation in the capable hands of an Australian-Dutch couple, Ben Bowler and Jildou Brouwer, who remained for several years until Sue found a charity, the Mirror Foundation, to continue supporting the project.

Regarding Mark's African mission, it would be a costly venture to ship heavy books overseas and fund his traveling expenses, shoestring as they may be. Money would need to be raised.

Early in 2007, via my website squarecircles.com and large Urantia mailing list, I started a fundraising campaign, teaming up with Mind, Body and Spirit as a non-profit to handle the donations. We worked side-by-side with Tamara Wood (Strumfeld) at Urantia Foundation and Merindi Swadling (Belarski), a second-generation Australian reader, who coordinated incoming funds on their end and arranged shipping. Our combined goal was $15,000.00. In the end a total of $16,825.00 was raised, half of it by squarecircles. Read "Seeding the Revelation in South Africa" here.

* * *

For almost eight months Mark sent me regular reports—a total of 12—which I posted unedited on my website and in email updates to the supporters. Then one day in March 2009 he emailed me with a demand: I must remove an article from my site about the Urantia Book Fellowship’s participation at the Delhi Book Fair “promoting a biblicized, idolatrous (in the eyes of Islam), rival, competing brand of the Urantia Book in the world’s third most populous Muslim country, India.” To Mark, this would precipitate world-wide bedlam in the Muslim world and prevent them from ever accepting the revelation—if not result in another 9-11 type attack. I saw things differently and did not remove the article, priding myself that at squarecircles we were liberal in promoting all efforts to share the revelation. He had his principles, but so did I, and we sadly came to a parting of the ways.

Sadly Mark never sent me another report, except for his very last one to me which he titled: “The Day the Reports Stopped Coming,” which I published uncensored on the site. Read all the reports here. Mark’s further reports were sent to a reader named Rick Warren, who shared them on several other Urantia sites. I never heard from Mark again, except for an obscure email a year or so later (I was blind-cc’d) that he was going undercover in the Muslim world, on a mission of sorts.

* * *

But now Mark is gone, and under very tragic circumstances. Still, I want to give him the credit he has earned and richly deserves, for all the good he did while he was here—seeding the Urantia revelation all over the world and introducing us to Sister Crescence and the wonderful work of the Sacred Heart Sisters in India! His legacy lives on!

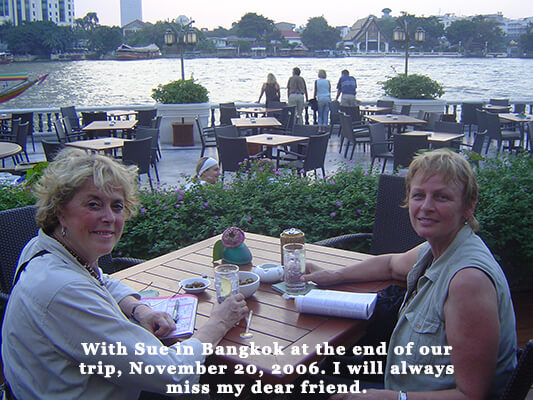

Another sad ending to this story is that my dear friend Sue Tennant had earlier passed away, in March 2018, of a heart attack. [Read more about it here.] It was a shock to all who knew her, wholly unexpected, and I miss her every day.

Both Mark and Sue had a lasting impact on my life, as they did on many others.

All images: Mark Bloomfield, Sue Tennant, Saskia Raevouri