Forumite Clarence Bowman

MORE MOVEMENT HISTORY

- The Contact Commission

- 533 Diversey Parkway

- The Plan for the Urantia Book Revelation

- Major Growth Steps in the Urantia Movement

- "I Remember the Forum"

- "Until We Meet Again"

- The Split: A Blessing in Disguise

- Sherman's 1942 Publishing Suggestions

- Sherman's 1942 Organization Suggestions

- The 1942 Forum Petition

- Sir Hubert Wilkins and the Urantia Book

- Forum Data and Apocrypha

- Childhood Days at the Forum

- Historic Urantia Newsletters

- Forum Days

- The Value of an Accurate History

- The Forumites

- Forumite Clarence Bowman

- Separate Publishing of Part IV

- The JANR Debate (2000)

- No Urantia Church-Not Yet!

- A Box of Chocolates

- 2003: Open Letter to Larry Mullins

- Urantia in Australia in the 1970s

- The Italian Translation Story

- La Storia de Il Libro di Urantiago

- The Urantia Book and Oahspe

- Webster Stafford's 1952 Urantia Report

Between 1923 and 1958 Clarence Bowman was associated with Dr. Sadler's Forum, the group that heard and read the evolving Urantia manuscript each Sunday at 533 Diversey Parkway in Chicago. The dates and contents of the meetings Clarence attended are recorded in his diaries, now published. Here his son Larry gives us a detailed account of the life and times of an ordinary man involved with an extraordinary phenomenon.

by Larry Bowman

Who was Clarence Bowman?

- A boy from small-town southern Kentucky who lived three different times in Chicago during important time periods: prior to World War I, the Roaring Twenties, and at the height of World War II and the booming postwar years.

- A high school dropout who years later attended a technical college and learned how to draw blueprints and design and build a house for his family.

- A fifty-two-year employee of the United States Post Office, most of the time in the Railway Mail Service—perhaps its longest-serving person.

- An avid attendee of the movies, going to silent films and then the “talkies” several times a week, whether in big cities or small towns.

- A regular attendee at church or other spiritual or religious services, including lecture series, searching for a presentation of God that inspired his beliefs.

- The earliest-known chronicler of meetings of the Sadler Forum in Chicago that led to the development of the Urantia Revelation.

- A loving father who often felt trapped in what he regarded was a loveless marriage, frequently wondering whether the best thing would be to do away with himself.

- A father who instilled in his son an unquestioning belief in a loving God and the idea that we were not the only world in the universe with human life.

These are some characteristics in the life of my father, Clarence Bowman, who lived from 1889 to 1959. During those years he saw the development of electricity, automobiles, airplanes, motion pictures, radio, and television. He witnessed the peak of railroad travel and lamented its decline. He enlisted for service during the Great War but never saw any action, being stationed in England and then going to France after the Armistice. With some friends he sailed across the ocean a few years later and revisited France and went on to Madrid. He was knowledgeable about other parts of the world but never visited any other country except Canada. With his mother he made a one-day foray across the border into Tijuana, Mexico. He had a great interest in history and lived through some tumultuous times on our planet.

My father was born on May 3, 1889, in Williamsburg, Kentucky. For point of reference, Charlie Chaplin was born April 16 that year, and Adolf Hitler was born on April 20. I have always been fascinated by the coincidence of the birthdates of two such famous contemporaries in my father’s life.

His birth certificate gives his full name as Clarence N. Bowman. The N. apparently stood for nothing (or Nothing?). I vaguely remember him telling me that it was years later before he chose the name of Norwood as his middle name. When that happened, and why that name, I cannot ascertain. The earliest record I find using that middle name is his draft registration card in 1917, when he was twenty-eight (or twenty-nine, because the record shows his birth date as March 3, 1888; I’ll get to that soon).

Clarence’s parents were William G. Bowman and the former Jeanette Smith. She often went by Nettie and was a housewife. I have not been able to find an 1890 census, but the one for 1900 shows that my grandfather was a “foreman river boom.” As best as I can tell, this has to do with working on the river for the lumber industry. Williamsburg is on the Cumberland River. I recall Dad telling me that his father eventually relocated to Washington State because of lumber. The 1910 census shows my grandparents and two aunts living in Anacortes in that state, and his occupation is listed as a boom man in the shingle mill industry.

Clarence had two sisters. Aletha (or Letha) was born in 1887 and Irene in 1895. Another child was born after Irene but did not live very long. I have not been able to find any information on that child and cannot remember the gender.

Letha married Charles Noyes in 1911, and he died in 1946; there were no children. She died in 1974 while jaywalking in front of an oncoming vehicle.

In 1918, Irene married Clarence E. Rydell, a widower. I will be writing more about Irene and her husband, who in his diaries is consistently identified by my father as C. E. Rydell and not as Clarence. Irene died in 1994, just short of her ninety-ninth birthday.

Neither of my aunts had any children, so my sister and I grew up with no first cousins on our father’s side.

I never met my paternal grandparents. Grandfather Bowman died in 1938, the year before I was born. Grandmother died in 1955 in Anacortes, long before I ever visited the West Coast. My first time to Washington was in 1972, and I got to meet my two aunts then. At the time they were living in separate rooms in a boarding house. With them I visited their parents’ gravesite, and I believe they are now both buried nearby.

Williamsburg is located in southeastern Kentucky just eleven miles north of Tennessee. Interstate 75 passes just to the west of town; Nashville is an hour away, and Lexington is about an hour-and-a-half north, with Cincinnati beyond that. But in 1889 there was no I-75. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad connected to Williamsburg in 1883 and stimulated growth. Williamsburg Institute, affiliated with Southern Baptist Convention, opened in 1889. It became Cumberland College in 1913 and in 2005 became University of the Cumberlands. Cumberland River, which originates in Tennessee in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, flows past Nashville and, beyond Williamsburg, flows over Cumberland Falls. Farther on it is the source of Lake Cumberland. Eventually it empties into the Ohio River near Paducah, Kentucky.

Founded in 1818, Williamsburg has never been a large town. When Clarence Bowman was born, the population was about 1,376. The present population is just over 5,000.

In August 2023 I visited Williamsburg as part of a larger visit to places in Kentucky associated with both my parents. (My mother was from the northeastern part of the state.) I had been to this town twice before: with Dad on a nostalgic visit (for him) in spring 1954, and a year later when my parents spent a night there on our way to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. But this 2023 visit was the most meaningful for me.

Sadly, I was not impressed with what I saw. It was pleasant to walk along the wooded shore of the river, with highway bridges passing high overhead. But walking down the few blocks of Main Street, I hardly saw anyone else. I couldn’t see that many businesses were really open. There was even a Rexall Drug Store sign whose presence I suspect was a touch of whimsy. Just a block or two past the “business district” on Main Street is the university campus. Many of the buildings seem to date from fairly recent years. Because it was between semesters, I hardly saw anyone around. I wonder how much interaction there is between town and gown when students are around. I left town wondering what Dad would think of the place now.

When I visited Aunt Irene in Anacortes in 1972, she told me there was a time when Clarence almost ran off with a girl who was in a circus. I remembered Dad mentioning this girl not long before he died, but I didn’t recall him telling me he was ready to go off with her. Nor do I quite remember what her act was, other than it did not involve animals. Writings of my father’s seem to indicate this occurred in 1903, when he was thirteen, and the girl was two years younger. This most likely happened while the family was still living in Williamsburg. I am certain his parents interceded and put an end to such thoughts.

The Bowman family remained in Williamsburg into the first decade of the twentieth century. I know that they lived in two more towns in Kentucky before all but Clarence moved westward. But which town came first I can only speculate.

On September 1, 1904, Clarence began working for the United States Post Office. In order to do so, he lied about his age and said he was sixteen instead of fifteen. He gave his birthdate as March 3, 1888. That “official” date of birth was to haunt him the rest of his life. On Ancestry I occasionally come across records providing conflicting birthdates. After Dad retired in November 1956 he tried setting the record straight by contacting various government agencies to notify them of his correct birthdate, among them Veterans Administration and Social Security. What responses he received did not indicate that he had to worry about possible criminal actions. His death certificate shows the 1888 date, and Mom corrected that on her copy.

But where did Clarence begin his longtime employment with the Post Office? I speculate that, because his grandfather, John Calloway Bowman, died on August 22, 1904, at his farm in Burnside, Kentucky, the farm went to his oldest son, William, my grandfather. And just a few days later, Clarence dropped out of school to begin working full time. Furthermore, Burnside, also located on the Cumberland River, was a center for shipping by rail and steamboat packet. The town included lumber mills, so William could continue to work in that industry.

Burnside is one of several places that lay claim to be home to the first Boy Scout troop in the United States. In 1908, two years before the Boy Scouts of America was officially organized, a woman from town organized a local troop of fifteen boys, using official Boy Scout materials she had acquired from England. A sign at the edge of town, which I saw when I was there in summer 2023, declares Burnside “Birthplace of Boy Scouts in America,” and an official state historical society marker commemorates the troop.

But the Burnside I saw is not the town where my father lived. In the early 1950s the entire town was relocated to higher ground due to the construction of Wolf Creek Dam, which led to the formation of Lake Cumberland. The lake had not reached its maximum size when Dad and I visited there in spring 1954. Today the town caters to lake traffic, primarily for boating and fishing. Lake Cumberland is called “The Houseboat Capital of the World”—but Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border might want to argue with them about that claim. The Burnside of my father’s time was likely slightly larger than now. The earliest census figure I can find is 1,117 in 1910, whereas in 2020 it was 694.

The Bowman family lived in one other town before leaving Kentucky before the end of the decade. Just a short distance north of Burnside is Somerset, the largest of the three communities where they lived and the town that impressed me the most on my 2023 visit to that part of the state. When they lived there, its population was around 4,000. Today its estimated population is over 12,000. I have no idea what prompted my grandfather to move his family to that town and cannot ascertain if there was any lumber industry in the area.

From reading my father’s diaries, it appears there were several relatives on his mother’s side in and around Somerset. Years later Clarence would make frequent visits to that town. It was during one such visit to Somerset with his mother, in the summer of 1929, that he met the woman who was to become his wife.

By 1910, all but Clarence were living in Anacortes, and he was in Hamilton, Ohio, near Cincinnati. When did everyone leave Kentucky? I have no idea. And by that year, Clarence was a railway mail clerk.

* * *

According to Wikipedia, the concept of sorting mail aboard trains was first put into practice on August 24, 1864, when a railway mail car began operating on the Chicago and North Western Railway between Chicago and Clinton, Iowa. The concept was successful, and the practice soon expanded to other railroads operating from Chicago, including the Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy; Chicago and Rock Island; Pennsylvania Railroad; and Erie Railroad. One of the very first railway mail clerks was British-born, future Santa Fe Railway hotel and restaurant entrepreneur, Fred Harvey. (Think of Harvey Girls.) He sorted mail between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Quincy, Illinois.

By 1869, when the Railway Mail Service was officially inaugurated, the system had expanded to virtually all the major railroads of the United States. In 1890, 5,800 postal railway clerks provided ser-vice over 154,800 miles of railroad. By 1907, over 14,000 clerks were providing service over 203,000 miles of railroad. RMS reached its peak in the 1920s and then began a gradual decline with the dis-continuance of parcel post service on branch lines and secondary routes. During the 1940s and 1950s, highway mail transportation became more prevalent, leading to the acceleration of abandonment of routes in the late 1950s (just when Clarence Bowman retired) and early 1960s. In 1948 RMS was re-named Postal Transportation Service. The last railway post office operated between New York and Washington, DC, on June 30, 1977.

“The life of a Railway Mail Service clerk was one of adventure, excitement, practice, and hard work. Clerks spent days away from home, traveling through the American heartland. They spent off time memorizing post offices and schemes.” (From www.postalmuseum.si.edu. Click on “A Day in the Life of a Railway Post Office Clerk.”)

Railway mail clerks were tested about every six months. Clarence’s diaries frequently mention him studying for exams and often refer to him studying “Indiana,” “Kansas,” “Montana,” or any such state.

Railway mail cars operated on passenger trains and were off-limits to the passengers on the trains. From 1900 to 1906, not long before Clarence apparently became a railway mail clerk, some seventy workers were killed in train wrecks while on duty in the mail cars, leading to demands for stronger steel cars. In all the years he worked for the Railway Mail Service, he was never injured in any train wreck, even though a train he was working on might have an accident, such as striking a vehicle. I don’t recall that there were ever any head-on collisions.

Since he was employed as a railway mail clerk by 1910 at the latest, and he continued to serve until he retired in November 1956, with the exception for two years or more in the Army during World War I, Clarence must have been a railway mail clerk for well over forty years, highly likely making him one of the longest-serving Railway Mail Service employees ever.

A few years ago I visited the California State Railroad Museum in Sacramento and particularly enjoyed the exhibit of a railway mail car. The guide who spoke about what it was like to work on such a car greatly enjoyed hearing me talk about my dad’s longtime service.

* * *

I do not recall my father ever telling me the circumstances of his leaving Kentucky and moving to the Cincinnati area, but I am guessing it happened at the same time the rest of his family moved west. No doubt his parents expected him to join them and his sisters, but Clarence thought otherwise. Perhaps the opportunity even came as an offer to make the transfer to Ohio.

At the time the family was living in Somerset, a passenger rail service ran through town, running between Cincinnati and Chattanooga. Possibly Clarence had the opportunity to work in a mail car on that route. He would have learned that the Railway Mail Service division office for that area of the country was in Cincinnati. And so, to that city he moved—specifically to nearby Hamilton, where he was living in a boarding house at the time of the 1910 census.

I have no information on the years he lived in the Cincinnati area. He apparently was transferred to Chicago in March 1912. On January 1 of the following year Clarence began keeping a daily record of his expenses, and occasionally he writes a sentence or two about something he did that day, such as going to a show or to church. This is the earliest version of what he regards as a diary. What I now have on hand are typed sheets for the years from 1913 to 1917, when he enlisted in the Army. These are sheets retyped from whatever he was using to record this information, usually one side of a sheet of paper representing a month, although sometimes a month went onto a second sheet. As the months passed, Clarence wrote more personal information.

During these years in Chicago he appeared to have a desk job with RMS at the post office building. The book, Lost Chicago, says that during this period the United States Post Office in Chicago was housed in the Federal Building, which occupied the block bounded by Adams, Jackson, Dearborn, and Clark Streets and was constructed between 1895 and 1905. The complex of eight stories had a dome set sixteen stories above the pavement. The rotunda was crowned by a dome one hundred feet in diameter, larger than that of the Capitol in Washington. I remember Dad pointing out the building to me one time, and he may have told me he once worked there. The building was demolished in 1965-66.

This first attempt at a diary shows Clarence living on Chicago’s North Side, most of the time at a boarding house on Buckingham Place and attending nearby Broadway Methodist Church. The church still exists at 3338 N. Broadway. Here, by 1914, he became acquainted with the Dyon family, which included the parents and their three children: daughter Anne and sons Albert and Ralph. Clarence and the younger son initially seem to have been the closer friends, but by September 1916 Clarence and Al were spending more time together. A few times they double-dated with two sisters. A woman named Fay Monroe—who showed up at Dad’s memorial service in 1959 after not having seen him for some thirty-five years—also starts being mentioned more often, and sometimes the three are out together or with additional people. Clarence spends Christmas 1916 with the Dyon family, and several others are also present. Al comes home with him afterward, and they vow to be in touch with each other five years from then. That evening they engaged in a conversation about the hereafter. The next evening, “Al Dyon came over and we talked about love affairs, short-story writing, etc.” On December 30, Clarence writes: “Al Dyon over in eve and we talked about sex life, stories, and generally interchanged ideas.”

Earlier, on the first of that December 1916, Clarence wrote this rather enigmatic statement: “Predict that one year from now I’ll be living in Spokane, Everett, or Seattle, Wash., and my life will be counting for more; will be something of a leader.” And on the following April 27, he said farewell to all his friends in Chicago and boarded a train that took him to Spokane.

In Spokane, where he had several maternal relatives, no sooner does he arrive in town than he begins working on a mail car on trains between that city and Missoula, Montana. “Back on the road again—hurray!” He worked overnight and then would spend the day in Missoula before returning to Spokane the next night. This could go on for two or three consecutive roundtrips before he had a few days off. By now, the United States had declared war on Germany and was involved in the Great War that had broken out in Europe three years earlier. On June 2, 1917, Clarence registered for military service.

The diary comes to a halt at the end of November. On December 14, 1917, he enlisted in the Army and was discharged October 7, 1919. He departed from New York for England on July 31, 1918. During the war he was stationed there the entire time and saw no action. Among the friends he made in the Army is Roy Vandergriff, whom Clarence in later years frequently refers to as Van. Our family was to meet Van and family a few times over the years.

Sometime after the Armistice, Clarence was stationed somewhere in France, most likely in or near Paris. And it most likely was from that country that he returned to the States in fall 1919 and ended up at his parents’ home in Anacortes, waiting for his next assignment from RMS. This waiting went on for several weeks, and his father accused him of being nothing more than a loafer. Clarence had long had a contentious relationship with his father, and all previous attempts of the son for a smoother association with his elder were always rebuffed. Either before Clarence received his new work orders or upon accepting them and leaving, Clarence had a complete falling out with his father. The two were never to see each other again, although there was occasional correspondence between them over the next eighteen years, until William Bowman died in Anacortes on September 22, 1938. Rather than display any anger, Clarence simply wrote in his diary: “Poor man, I guess he was glad to lay down the burden of life.”

On the Ancestry website I saw that the 1920 census says Clarence was a boarder in Cass, Indiana, and was listed as a railway mail clerk. I am quite certain I had never heard that before. Wikipedia says it’s an unincorporated community that had a post office until 1955. It is located several miles south of Terre Haute on a country road to the east of US 41, the main highway between Chicago and Miami, Florida, long before the interstate highway system was built. I cannot imagine why he was living there. I should think it wasn’t long before he was back in Chicago, which is where he was when he resumed his diary in 1922.

* * *

There are no known diaries of Clarence Bowman between the end of November 1917 and January 1, 1922. His first entry of ’22 gives no hint that there were any, or even that this was his first writing after such an absence. This year he began using a standard book 2.5" x 4". He continued with this size until 1941, when he momentarily misplaced the volume and then switched to a larger size, 3.5" x 6". This larger size he continued using the rest of his life, until 1959. The cover of The Urantia Diaries of Clarence Bowman shows a photo of all these diaries stacked together. These may be government-issued diaries, but I am not really certain. Each volume contains postage rates and population and weather information. Some volumes put Saturday and Sunday on the same page, thus narrowing the opportunity for writing anything of real substance. In the published book with scanned images of the pages, you will find that Clarence had to be succinct in his writing—sometimes too succinct. He will mention many a name without indication as to whether or not he has ever brought up that person before. When I started writing my own diary in January 1957, I initially used these volumes; but after two years I found them restricting and switched to writing on 8-1/2x11 sheets.

As he begins the 1922 volume, he lists his address as 723 Barry Avenue in Chicago. This is just east of Clark Street roughly halfway between Diversey Parkway and Belmont Avenue. He gives his business address as “11th floor, P. O. Bldg., Chicago.” I am not certain what building he means, as the Federal Building, where he apparently worked before, did not have that many floors (despite its high dome). What is now called Old Chicago Main Post Office opened in 1921 at 433 W. Van Buren Street, on the west side of the South Branch of the Chicago River. Wikipedia only mentions nine stories. In 1932 the building expanded into the huge structure that it now is, in its heyday being the largest post office building in the world. The size was needed in order to handle the mail-order businesses of Montgomery Ward and Sears. The building is noticeable not just for its size but also because, when it opened, a “hole” was left in the structure for the future Congress (now Eisenhower) Expressway (I-290). In 1997 the building was vacated by the United States Postal Service, the successor organization to the United States Post Office, and is now used for offices of many companies.

The 1922 diary shows that, in case of accident or serious illness, one should contact Clarence’s mother in Anacortes and the Superintendent of Railway Mail Service in Cincinnati. I find it interesting that, although now once again living in Chicago, he reports to the Cincinnati office.

As the year began, Clarence was at the midnight show of a movie theater with his sister Irene and her husband, “C.E.R.” I mentioned earlier that the C stood for Clarence, which my future father never mentions in his diary. The three returned home at 2:10 a.m. and had something to eat. From what I was able to figure out, Clarence Bowman and the Rydells were sharing an apartment.

On that first day of the new year (and a new diary), Clarence spent the afternoon with Al Dyon, his good friend from pre-Army days. “Then I went out to see Prof. Sam. B. Groves in Wilmette, Ill. and took dinner with him. We talked over Williamsburg, Ky, days. Home 11:30 p.m.”

This is only one of two times Clarence gives Mr. Groves’s first name; every other time it is S. B. Groves. In 1880 Samuel Groves was twelve and living with his parents, Samuel S. and Sarah T. Groves, in Canaan, Ohio. Groves married Clara L. Anderson in Ashland, Ohio, on June 29, 1891. He graduated from seminary at College of Wooster in Ohio that year. In 1902-03 he was a Presbyterian minister in Ashtabula, Ohio. City directories for 1912 and various years the following decade showed him and his wife living at 1223 Wilmette Avenue in Wilmette. Clara was a widow at that address in 1935. Groves seems to have died the year before. While I could not find a 1900 US Census showing where Groves was living, I have come to the conclusion that he was living in Williamsburg then and was probably a minister at a church that Clarence’s family attended. However, since Clarence occasionally refers to him as “Professor,” I wonder if he might have also been associated with what became Cumberland College in Williamsburg.

Up to this point, Clarence has mentioned the Groveses only once before in his diary, on May 28, 1913, when he was living in Chicago for the first time. In 1922 he mentions Groves again just three days later, on January 4, when he has lunch with “Sam’l B. Groves at Graeme Stewart School.” This was then a public elementary school at 4525 N. Kenmore Avenue in the Uptown district and was home to students for more than one hundred years, including actor Harrison Ford and director William Friedkin before closing in 2013 due to low enrollment. The building is now luxury condos called Stewart School Lofts. Groves is not mentioned again in the diary until November 1, 1923.

By April 1922, Clarence was living on Chicago’s South Side and was to remain there until he left Illinois later in the decade. He resided in what was then still a white neighborhood. He seemed to go out with a different lady almost every night. Every Sunday he was going to church, quite often a Unitarian one. He and Al Dyon attended a lecture by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. By the end of the year he settled into a room at 6120 S. Ellis Avenue, which is just south of the University of Chicago and a few blocks west of Jackson Park.

In a year-end wrap-up (the only one I ever saw Clarence write), he mentions that Irene and her husband were now living apart, an act which was dividing the family, with my future father and his sister on one side, and their parents on the opposite.

As for his work, he states he is clerk in charge of the Pittsburgh, Akron, and Chicago RPO (Railway Post Office) on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. As best I can figure out, he was running between Pittsburgh and the little town of Fostoria, Ohio, which was on the mainline of the B&O. He maintained a room in Fostoria, where he would stay between runs before eventually deadheading back to Chicago and resting for a few days. One reason he was living on the South Side was so that he could get off at a station on 63rd Street.

On November 1, 1923, Clarence “had lunch with Mr. S. B. Groves, formerly of Williamsburg, Ky, and upon his insistence I made a couple of speeches to his class of boys.”

I am indebted to Jesse Thurston for researching newspaper archives and sharing with me what he found. “Mr and Mrs S. B. Groves were school teachers in Wilmette. Mr. Groves taught ‘manual training’ and Mrs. Groves taught history. They also worked as camp counselors in the summertime. There is record of a Rev S. B. Groves in Williamsburg, KY in the early 1900's—perhaps this was Mr. Groves' father. No evidence I've found that S. B. Groves was a doctor or professor. Additionally, my hunch is that the ‘Mr. Nichols’ mentioned later on in Clarence's diary [March 21, 1926] was the Groves' son-in-law. John Nichols married Helen Groves, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. S. B. Groves, and they had a son, John Groves Nichols, in 1921.”

From my own research on Ancestry, I know now that the S. B. Groves in Williamsburg whom Jesse found was the same man and not his father. Groves was a generation older than Clarence.

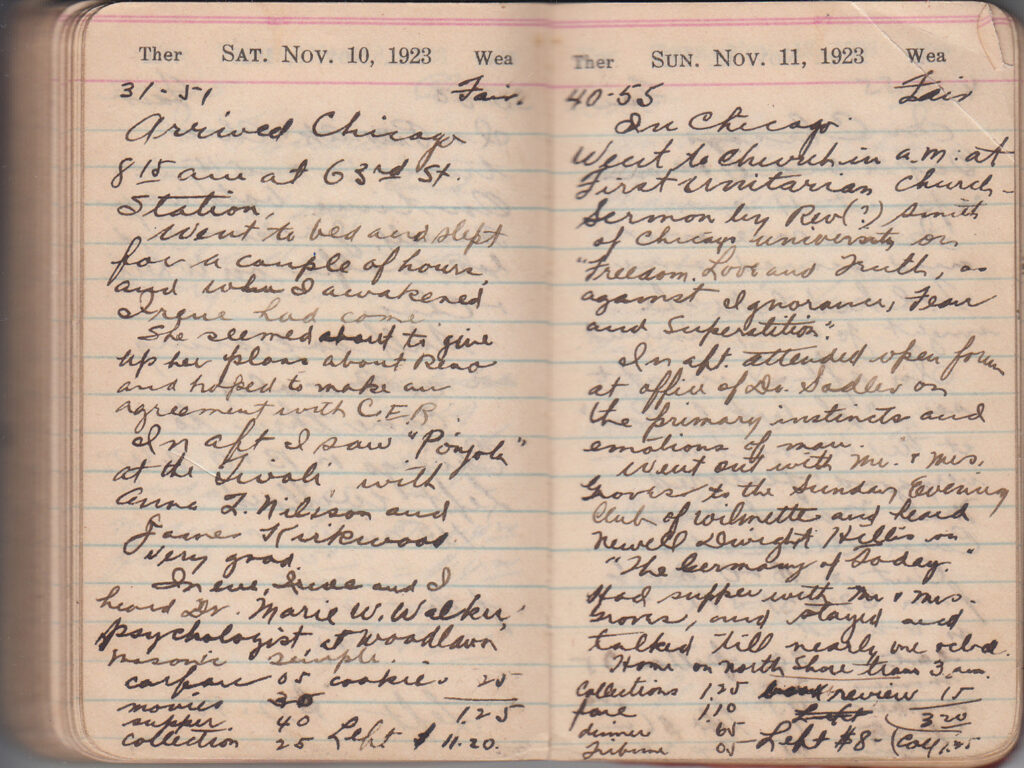

I remember my father telling me that when he saw Mr. Groves on this occasion, he mentioned he was suffering from migraine headaches. Groves suggested to him that he see Dr. William S. Sadler. Dad said he did, and Sadler then invited him to the Forum meeting the following Sunday, which would be November 11.

However, his diary does not corroborate this story. There is no mention at all of any migraines or of seeing Dr. Sadler in between those two dates. On November 11 he attends his first meeting of the Forum, which appears to be the first time Clarence ever met either Dr. William or his wife, Dr. Lena Sadler. And Clarence apparently was there with Mr. and Mrs. Groves, because he went out with them afterward and did not return to his South Side room until the middle of the night.

And thus began Clarence Bowman’s long association with the Forum that eventually helped foster the Urantia Revelation, the publication of the Urantia Book, the creation of Urantia Brotherhood, and the Forum transitioning to the First Urantia Society.

* * *

On December 9, 1923, Al Dyon attended the Forum for the first time. At the beginning of his 1924 diary, Clarence indicates he now reports to a supervisor in Chicago and no longer Cincinnati. On March 2, 1924, Clarence’s sister Irene was at the Forum; Mr. and Mrs. Groves were also there. On March 14, Clarence met Charlotte Norton, Albert Dyon’s future wife. On October 21, Clarence enrolled at Chicago Technical College for a drafting course and was to continue with the college for other courses for a few years. Chicago Tech was a private junior college that was founded in 1904 and closed in 1977. The school was located on S. Michigan Avenue.

It was always my understanding that Clarence was at the first meeting of the Forum when on December 14, 1924, Dr. Sadler told the group about his longtime patient, the so-called Sleeping Subject. On that date he writes in his diary about the “wonderful revelation from Machavalia [sic] and ABC.” However, from what I learned at a presentation by Marilynn Kulieke on February 11, 2023, celebrating the centennial of the first meeting of the Forum, it apparently was the previous 1924 Sunday, on December 7, that Doctor likely first mentioned the patient and the spiritual visit that occurred the preceding February 11 [1924] to what we now know as the Contact Commission. On that occasion, it was Machiventa (not Machavalia) Melchizedek and ABC the First who suggested to the Commission that they use their new Sunday afternoon group to ask questions about such matters as God, the universe, life after death, and similar topics. Sadly, Clarence had missed that day, as he was feeling “dull and listless” and did not go to church or to the Forum. Now knowing that, I wonder if Clarence was ever able to participate in the project, being able to submit his own questions.

The end result was that 181 questions were submitted, and in January 1925 the “answers” to those questions began emerging in what became the earliest versions of the Urantia Papers. I will let the diary entries speak for themselves on the original titles of the papers and how, over the years, upon further questioning from the Forum, the papers were expanded and eventually became how we now know them.

In the meantime, Irene Rydell established residency in Reno and was divorced from C. E. R. on April 8, 1925. She returned to Chicago in May and was dating someone named Jack. Actually, they had been dating even while she was separated from her husband, before the divorce. In September, Clarence wrote, “I hate to think it, but Irene and I seem to be growing more and more apart in sympathy, ideals, and everything.”

As for Mr. and Mrs. Groves, they do not appear to have attended any Forum meetings after 1924, so they were not involved in the development of the Urantia Revelation. Yet it is interesting that their son-in-law, John Nichols, is mentioned being present on at least one occasion in March 1926.

In June 1926 Clarence purchased his first automobile, a used Willys Knight; and after taking a few driving lessons—which did not seem to help any—he was soon off rear-ending other vehicles and occasionally tapping pedestrians. He finally met his match on October 8, 1928, when, with three passengers, “I went driving and had accident in Washington Park. Two complaints of reckless driving placed against me. I spent the night in police station at 48th & Wabash. My car ruined.” He was bailed out of jail the next morning by postal coworkers.

On November 4 Clarence moved from Chicago to the small town of Deshler, Ohio, which was on the mainline of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. For a while his mail car run was between there and Pittsburgh, but on occasion he came to Chicago for a few days (and stayed with the same landlady) and was able to take in some Forum meetings. He was in Chicago for the trial regarding the auto accident, but the complainant never showed up, so the complaint was dismissed. But then a civil suit was filed against him to recover damages to the other vehicle. Whatever eventually became of these legal actions are never specifically mentioned in the diaries, so I can only assume that they, too, were dismissed.

I remember Aunt Irene telling me in 1972 that the driver of the other vehicle who Clarence ran into was rumored to be a member of the Chicago Mob, so that was the main reason that her brother changed his residency to Deshler. With this move, Clarence was to remain a resident of the state of Ohio for nearly fifteen years. When Clarence Bowman moved back to Chicago during the middle of World War II, much had changed in his life.

* * *

The tenth anniversary of the Armistice prompted Clarence to get in touch with his onetime Army buddy, Roy Vandergriff, now a Methodist minister living in Edgerton, Ohio, a few miles to the west-northwest of Deshler near the Indiana border. In January 1929, Clarence spent two nights in Edgerton with Van and his family, after which he wrote, “So ends the visit of pleasure with another friend who has gone on in the world. I feel lonely, living myself this way.”

Earlier that month, Albert Dyon and Charlotte Norton told Clarence of their engagement. That fall he received an invitation to their wedding, but I do not see that Clarence attended. This was probably because of his work. I have not been able to find a marriage record for Al and Charlotte, so I don’t know when the wedding happened. The 1930 census shows them as married.

Although his mail route at this time did not include Chicago, in spring 1929 Clarence made occasional one-day trips to attend the Sunday Forum meetings.

In June 1929, Clarence left Deshler for Chicago in his Oldsmobile, met his mother coming in by train from Washington, and began several days of driving through Indiana, visiting with relatives along the way, and arriving in Somerset, Kentucky. Here they stayed with Grandmother’s niece, Lena, and her husband, Dudley Denton. On the 29th Clarence mentions Virginia Womack for the first time. She had just graduated from what was then called Eastern Kentucky State Teachers College in Richmond and was visiting with her roommate, Edna Denton, Lena and Dudley’s older daughter. A large group went to a picnic and “Had mighty good time.”

It is not clear to me whether that was the only day Clarence and Virginia were ever together before he eventually returned home to Deshler, taking his mother with him. Here Mamma stayed with him for several days before Clarence drove to Chicago and put her on a train back to Washington. I remember a conversation once between my parents in which Mom said she never met any of Dad’s family, and he remarked that his mother was with him that day in Somerset when he and Virginia first met. I gathered that there were too many people in attendance for Virginia to know his mother was there.

The next mention of Virginia is August 12, when Clarence wrote her a letter. His next references to her are on January 14, 1930, and again on March 27, when he wrote more letters to her. On April 11 he arrived in Harlan, Kentucky, several miles east of Williamsburg. Virginia was teaching school at nearby Coxton. He walked out to visit her and on the way back was held up and robbed. In another year Harlan County was to become notorious for an almost decade-long struggle between coal miners and union organizers on one side and coal firms and law enforcement officials on the other. Before this “Harlan County War” ended, numerous miners, deputies, and bosses would be killed. This unrest played an important role in the development of organized labor.

On April 13, Clarence declared his love for Virginia. The next time they were together was on May 19, when he met her at her alma mater in Richmond, Kentucky, and had lunch with her, Edna Denton, and Virginia’s sister Eloise, then a student at Eastern Kentucky. He and Virginia then drove to her parents’ home in Oldtown in Greenup County in the northeastern part of the state.

I always understood that Oldtown got its name for being the first white settlement in Kentucky, but I see that that distinction belongs to the city of Harrodsburg, which was founded in 1774. Oldtown was first settled in the eighteenth century and was probably named for the remains of a Native American settlement. There were several iron furnaces surrounding Oldtown. The cemetery includes the grave of Lucy Virgin Downs, 1769-1847, the first white child born of American parents west of the Allegheny Mountains, in what is now Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in the southwestern part of the state. She moved with her family to Kentucky in 1790 and lived the last forty years of her life in Oldtown. I understand her brother is an ancestor on my mother’s side.

Oldtown is an unincorporated community on Kentucky highway 1 a few miles south of Greenup, the county seat. As a child, I remember this road was gravel until about 1948, when it was finally paved. The community had a fourth-class post office from 1900 to 1992. At the time that Clarence met Virginia’s parents, her father, Walter Orin Womack, was postmaster, and the post office was housed in a general store he had built. My grandfather may very well have been the original postmaster, as he and Mary Carnahan married in 1900 and the 1900 census identifies him as a merchant, rather than farmer.

Clarence stayed with the Womacks until May 25, when Virginia rode back with him to Deshler. (He does not make it clear about the sleeping arrangements, but since he was living in a boarding house, I imagine he found a room for her there.) On the 28th they drove to Defiance, a town a few miles to the west, also on the B&O mainline, to see fellow RMS employee Arthur Latchaw about helping her to get a teaching position. (Latchaw was on the Defiance School Board.) Clarence wrote, “The more I see of VW the more I am impressed with how wonderful she is.”

He took her back to Oldtown on May 29 and returned home on June 1. The next day he wrote, “Felt fatigued from the intense driving home last evening. Also terribly lonely for Virginia. I don't believe I have ever cared for a girl before as I do for her.” On another visit to Oldtown, on July 1, Clarence proposed to Virginia, and she said yes. A few days later, back in Deshler, he wrote, “Felt tired and listless and terribly lonely. Life has little meaning any more when Virginia is not near.” On July 14, while in Chicago visiting with Al and Charlotte Dyon, he bought an engagement ring.

A few days later, Clarence drove over to Defiance to confer with Arthur Latchaw about purchasing a house he had for sale and ended up signing papers. (Latchaw’s father was president of Defiance College from 1896 to 1902; he died in Michigan in 1928. There is a Latchaw Drive in Defiance. I imagine it was named after one or more in the family, but I do not know for certain.)

On November 29 Clarence was visiting his fiancée in Oldtown. “This is the day Virginia and I first planned to get married, but alas for our plans.”

On June 6, 1931, Clarence was visiting Oldtown when Virginia received a phone call from Somerset that Frank and Ethel Denton had drowned in a lake. They were Edna’s brother and sister. Clarence and Virginia headed to Somerset and spent two nights. The bodies were never recovered.

Clarence Bowman and Anna Virginia Womack (her full name) were married in Oldtown on August 24, 1931. The best man was Roy Vandergriff, and the bridesmaids were Eloise Womack and Edna Denton. On September 1 the newlyweds left Oldtown for Deshler and on the 7th moved into a rented furnished house in Defiance at 618 Washington Avenue. (The house that Clarence had bought from Latchaw was not available to move into that first year because of a tenant renting it—a professor at Defiance College.) Over the next twelve years Clarence and Virginia were to live in four different houses during their time in Defiance.

* * *

Defiance, Ohio, is on US 24 approximately halfway between Toledo, Ohio, and Fort Wayne, Indiana. It gets its name from the fort that was built by General “Mad” Anthony Wayne in 1794 during the Northwest Indian War at the confluence of the Auglaize and Maumee Rivers. Wayne surveyed the land and declared, "I defy the English, Indians, and all the devils of hell to take it.” Today a pair of cannons outside the public library on the Maumee River overlook the confluence and mark the location of Fort Defiance, along with a mounded outline of the fort walls. From this fort General Wayne led his troops down the river and fought the Battle of Fallen Timbers, where Native American tribes were defeated, securing for the United States the Northwest Territory, now the states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. During the War of 1812, Fort Winchester was built along the Auglaize River just south of this spot.

Interestingly, a park along the north side of the Maumee, opposite the mouth of the Auglaize, has a sign definitively identifying this spot as the birthplace in 1712 of Pontiac, the Native American war chief who fought against the colonists during the French and Indian War. He is believed to have been born between 1712 and 1725, but where he was born is in dispute. The former automobile was named after him. I learned to drive in a Pontiac. Also in this park is a sign indicating where an apple tree (now gone) had been planted by Johnny Appleseed.

In 1822 Defiance was laid out as a town. In 1845 it was made the county seat of the newly created Defiance County, and in 1881 it became a city. Defiance became a market for the farm produce of the Maumee valley. Manufactures came to include screw machine products, hand tools, ferrous castings, and glass fiber. The 1930 census showed the population at 8,818.

Upon settling in Defiance, the newlyweds soon started attending the Presbyterian church, which became an important part of their social and religious life during their years in town. It is interesting to read in Clarence’s diaries how people would just drop by for unannounced social visits, and Clarence and Virginia would often do the same themselves. Among their earliest visitors were Mr. and Mrs. Adrian John. “Addy” was a fellow RMS employee. When I returned to Defiance in 1968 to become librarian of Defiance College, the mayor of Defiance was Addy John’s daughter, and she told me she remembered our family.

Earlier in August 1931 Clarence began the new run on his mail route that involved deadheading back to Deshler—soon to be Defiance—after completing two roundtrips between Chicago and Pittsburgh. This was to be his run for the rest of his RMS career, although the deadheading ceased after the family moved to Chicago in 1943. In each city he would stay overnight—or rest during the daytime, depending on the timing of his trains and whether they ran overnight or during daytime hours—at “official” RMS dormitories or approved hotel facilities. Initially in Chicago, his stays were at the Grace Hotel, which was at the southeast corner of Clark and Jackson Streets. This would not be too far walking distance from Grand Central Station, a monumental edifice at the southwest corner of Harrison and Wells Streets, owned by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. The station was razed in 1971.

Not even a month after moving to Defiance, Clarence and Virginia traveled to Chicago and stayed with Al and Charlotte Dyon for a few days. This was Virginia’s first visit to that city, and I believe it was the first time for her to meet her husband’s longtime friend and his wife. In July 1932, a now pregnant Virginia, with Clarence, paid another visit to the Dyons. In late August, Clarence and Virginia started moving into the house they owned at 400 N. Clinton Street in Defiance, and on October 23, 1932, daughter Carolyn Anne Bowman was born in a room on the second floor. (For some reason Dad in his diary lists her birth name as Caroline. He soon learned how to spell his daughter’s name.) Clinton Street was the main street through town, although the house was located north of the river; the business district was south of the Maumee. The college was two blocks north of the house on Clinton.

In 1933 Chicago celebrated the centennial of its incorporation as a city by hosting the Century of Progress Exposition on the lakeshore site where McCormick Place, the convention center, now is. This was also known at the Chicago World’s Fair. Clarence visited it one day in July during a layover in the city, and then in October, he and Virginia spent three days at the fair while staying with the Dyons. (Carolyn was left at home in Defiance with a babysitter.) The fair was so successful that it was held over for a second year.

By October 1934 Clarence was now staying at the Fort Dearborn Hotel in Chicago in between his train trips. This was at 401 S. La Salle Street. It is now a commercial office building known as La Salle Atrium.

On May 14, 1935, while in Pittsburgh, Clarence sprained his back and had to go to Marine Hospital for examination and treatment. He remained in the hospital until June 1, when he was dismissed and returned home to Defiance. During those days in the hospital he expresses his belief that Virginia and maybe even Carolyn would come to visit him, but this did not happen. He returned to his road trips on June 11. This injury had a lasting debilitating effect on his health, and he was never again as physically sharp as he had been. Still, he was to remain a Railway Mail Service employee for over twenty-one more years.

The following August 21, after a road trip, he attended the first Forum observance of Jesus’ birthday. Part IV, otherwise known as the Jesus Papers, had come all at once earlier that year and before long were made available to the members of the Sunday group. I believe this was his first time at the Forum in a few years.

By this time, Clarence and Virginia had become dissatisfied with their house on Clinton Street and began to talk about selling and perhaps building their own home somewhere else in town. While on a trip to his in-laws in Oldtown that July, he began drawing plans for “our projected house.” On October 3 he writes, “In aft. Va. [Virginia] and I discussed finances and the possibility of ever being able to have a home with any comforts. It looks rather dark at this time and we can scarcely see daylight ahead. … Va. and I both were on the border of hysteria all day.” In May 1936 they sold the house and on June 30 they moved to a rental property at 763 Harrison Avenue in Defiance. This backed up to a different railroad line, not the B&O. Carolyn had the dimmest memories of trains roaring by but apparently not disturbing her or anyone’s sleep.

It was during the almost two years the family lived in this house on Harrison that neighbors practically across the street at #804 were one of the two Black families then living in Defiance, although I do not see that Clarence mentions this. Only in the past year have I verified that it was the Derricotte family. The father was a cobbler, and his oldest son, Eugene, graduated as valedictorian at Defiance High School and then went to University of Michigan, where he played football. He became the first African-American to play on the team’s offensive backfield. I remember Carolyn listening to a football game in about 1947 and saying that Gene Derricotte was from Defiance. He scored a touchdown in the 1948 Rose Bowl. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Derricotte) Gene’s brother Ray was treasurer of Defiance College when I became the college librarian in 1968, and I remember chatting with him about his brother during my first week in my new job. Interestingly, Ray and Gene died just a few months apart within the past two years.

My late friend Sally, who I am about to mention, told me the other Black family in Defiance at the time was headed by jazz musician Milt Buckner. I had never heard the name, so I had to look him up. (https://www.nytimes.com/1977/07/30/archives/milt-buckner-dies-musician-composer-a-longtime-pianist-and-organist.html)

Clarence does not mention this in his diary, but in about 1940 their former house at 400 N. Clinton Street was moved across the street and up a block to another street off Clinton. From 1963 until her death in January 2024, that house was owned by a longtime family friend, whom I shall just identify as Sally. She was two years younger than I and apparently was the first baby I ever saw. Dad writes: “Larry didn’t know what to make of it [the baby].” Sally’s parents are mentioned frequently in these diaries but not in any connection with the Forum or the Urantia Book. Her father was the son of the publisher of the daily newspaper, and when I became librarian of Defiance College, the grandfather was on the college board of trustees. Towards the end of my five years at DC, Sally’s dad and then she herself each joined the college administration, working in Defiance Hall. My domain was Anthony Wayne Library. “Mad” was not part of the name.

My mother, her oldest grandson Jeffrey Kendall, and I stayed overnight in Defiance in 1966 and visited Sally in her house. We pointed out to Jeff the room where his mother was born. I have no memory of that visit to the house, but I do recall Carolyn and I seeing it in summer 2010. It is now a Historic Home of Defiance and dates from 1900.

On August 7, 1936, Clarence traded the Oldsmobile for a Plymouth. This is the car I remember our family having when we moved from Defiance to Chicago.

On September 18 he bought a lot on Wayne Avenue from “Mrs. Oelke.” Louise Oelke, born in Alsace-Lorraine, was the widowed head of a family that also included two grown sons whom Clarence always called Fritz and Gus. The street was named after General Anthony Wayne.

On July 20 of the following year, Clarence returned from a road trip to learn that Al and Charlotte had been in town. That August, Clarence and Virginia signed papers for a loan to build the house on Wayne Avenue. They received a permit to build the house, and excavation began on the lot on the 12th.

In addition to designing the house and drawing the blueprints, Clarence was active in the construction. He did the wiring and helped with the framing of the windows. His courses at Chicago Tech years earlier had prepared him for this project, in which he was assisted by professional contractors and others, including Gus Oelke. Still, financial concerns weighed on his mind. On January 30, 1938, he wrote: “All the way to Chicago, and good part of trip east, had low sinking feeling in stomach. Don’t know when I ever felt more depressed or Life more futile than now.”

April 5, 1938, was moving day to 1129 Wayne Avenue, a two-story red brick house whose most interesting feature probably was the laundry chute that ran from the second floor all the way to the basement. What I remember most was the fireplace in the living room. There was also a veranda atop the garage.

* * *

During the 1930s in Defiance the family visited Kentucky almost yearly, mainly to Oldtown and surroundings. Clarence always referred to his mother-in-law as Mother Womack and his father-in-law as Mr. Womack. I do not see that Clarence had any close connection to my Grandfather Womack, despite being closer in age to him than he was to his own wife. There was seventeen years difference in ages between Clarence and Virginia; he was forty-two and she was about two weeks from turning twenty-five when they married. Walter Orin Womack was born in 1876 and Clarence in 1889. Also, both men were employed by the United States Post Office—or perhaps Grandfather was just under contract with them to maintain the Oldtown Post Office—but I see no indication of any “trade talk” between the two men. Still, I never recall any mention from Dad that he did not get along with his father-in-law.

Other than the wedding in August 1931, perhaps the family’s most memorable moment during any visit to Oldtown occurred on July 26, 1938, while Virginia; her mother; sister-in-law Mae Womack; and the latter’s two children, Richard and Joan, were at Mae’s house when an intruder burst into the house during daylight. The man was completely naked and said he was Jesus Christ. In summer 2023 my cousin Joan, then ninety, told me that Virginia calmly put some clothing over the man. The sheriff’s office was called and he was taken to Greenup, the county seat, where he was found insane and sent to an institution. Clarence and Carolyn did not personally witness this episode, but by evening the story was being told and retold among all the relatives. It is a story I have heard many times over the years. Joan, just a few months younger than my sister, was the last surviving witness to the episode, but now even she is no longer with us.

The next day, the family took a four-day trip to Somerset, Cumberland Falls, and Williamsburg. As far as I know, this was the only time Carolyn was ever to those places.

In autumn 1938 Clarence began writing some sad entries in his diary. October 9: “I don’t recall a day when I felt so low and depressed, so heart-achey, and life so futile. Va. and I sort of smoothed things out after we went to bed.” October 30: “In eve I listened to radio presentation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds. Vivid story of cosmic disaster. I felt low and depressed all day and almost at my wits’ end.” (This is the famous Orson Welles broadcast the night before Halloween that frightened many listeners, but Clarence knew that it was only a dramatization.)

That December 20, Clarence told Virginia he was going to Deshler, but what he really did was visit a lady friend from the past whom he had once felt very strongly about. She had recently become a widow and was now living in Dayton after having been in Canada for several years. On that occasion, Clarence learned the woman had never felt the same way about him. On December 31, “Came home and found Virginia almost in tears. In eve she told me had discovered my deception about my supposed trip to Deshler on Dec. 20.” By now, Mom was pregnant with me. January 5, 1939: “In eve Va. said she almost wished we weren’t going to have another baby. A repercussion of my recent defection, I guess.”

Amidst all this tension, I was born on June 14, 1939, in the local hospital and was given the name of Lawrence James Bowman.

And on July 31, Albert and Charlotte Dyon, after two miscarriages over the years, became the parents of Jane Dyon. Dad does not mention this date in his diary nor even her name for a long time, although he did see her a few times as an infant.

December 10: “At night Virginia and I tried to reconcile our differences which have accumulated during the last few years. I don’t know how successful it will be, but we have at least made a start.” April 18, 1940: “In eve we tried to talk things over and see what was making us so uncongenial, and it wound up by her bringing up Dec. 20, 1938, so from then on, reason was out of the question. Each day of my life dawns with me asking, ‘How can I possibly live through this day?’” May 1: “I have determined to be something besides an assistant housemaid, no matter what comes of it. My self respect demands a change.”

Nineteen forty was a depressing year as far as their marriage was concerned. They did not communicate much and there was lots of tension at home. Several times Dad wondered if life was worth living. He often had trouble sleeping, thinking about his situation, and it affected his health.

February 11, 1941: “I wonder if I am to blame for the lack of sympathy apparent in our married life. I used to think I was the most sympathetic person alive, and I could always see the other person’s side clearer than my own. But at this time I seem always to be in such a state of confusion—it is like being in a cage that is being rapidly revolved. Everything is a blur. Sometimes I think mine is a case for a psychiatrist. All I seem to live for is for the children’s sake—certainly for no happiness I have apart from them.”

July 20: “Last night was one of the most miserable nights I ever spent. I lay awake, wondering what on earth I have to live for. Only for Mamma, Letha, Irene, Carolyn, Larry, and a few others who believe in me I’d take the quick way out. But you can’t let those down who love you and think you’re a great guy. When two people, supposedly intelligent and considerate of each other, can’t compose their differences, what chance have they for anything but misery?”

August 1: “Sometimes I wonder what the future holds for our marital enterprise. V. can never find a kind word for me anymore. Everything is complaints—money shortages, etc. One would think I was the worst husband on earth. I can’t produce dollars out of a hat. At bedtime, she did say she was sorry.”

September 16: “I declare, when we discuss finances, it is like a red rag to a bull. Our situation is precarious. I see no money in future for clothes, dental or medical care or any of the minor luxuries of life. It all goes for fuel, food and insurance.”

November 20: Thanksgiving Day: “I suppose someday I will be able to look back to this day and say I had something to be thankful for, but today I have what might be called ‘nearsightedness’ as to the latent pleasures of life. We gorged the body but starved the soul. Had turkey and all that goes with it.”

On June 11, 1941, Dad and Carolyn began a trip to Washington State. On this day they took the train to Chicago, Carolyn’s first time on one. Late the next day they started driving west in a rental car. On the 19th they arrived in Anacortes. “Saw Mamma after 12 years, Irene after 11 years, and Letha after 22 years.” (Sadly, this trip was to be the last time Dad and his mother ever saw each other. She died in 1955.)

September 13, 1941: “In eve. Dicky Ryan threw a roller skate and inflicted a severe cut below Larry’s left eye. I took him to Dr. Mitchell’s to have it dressed.” Dicky was the second child and oldest son of the Ryan family featured in the 2001 book and subsequent film, The Prize Winner of Defiance, Ohio. I believe the family was then living on the street behind us. Dicky grew up to become a minor league pitcher. He developed his skills very early, it seems. Sometimes when I mention the name of the town where I was born, the name elicits a comment about this book or the movie. The book’s subtitle, How My Mother Raised 10 Kids on 25 Words or Less, explains how a housewife of a factory worker who spent his money on liquor would enter contests on TV, radio, newspapers, or direct-mail ads and win “every appliance her family ever owned, not to mention cars, television sets, bicycle watches, a jukebox, and even trips to New York, Dallas, and Switzerland.” The movie starred Julianne Moore and Woody Harrelson.

Unfortunately, it was not filmed in Defiance. The director, Jane Anderson, thought the Defiance of the early twenty-first century had changed too much from the one of decades earlier, so she chose a different location. I have no memory myself of the Ryan family, but on visits to Defiance we would hear about Evelyn Ryan’s remarkable success from family friends.

* * *

Before I continue, I should mention a couple of incidents involving my father he could no longer get away with were he living today. One New Year’s Eve he shot his service revolver into the air to celebrate. And then there is the story about Blackie the cat. The family adopted him some two years before I was born. From the few references to the cat I can find in the diary, he apparently was mostly an outdoor cat, generally not allowed indoors. Family lore is that, around the time that I was born, Blackie bit Mom, and Dad had Fritz Oelke shoot him with his gun. When Carolyn questioned about Blackie’s whereabouts, she was told that the cat must have run away. Only later did she learn the truth about what had happened to him. Carolyn did not appreciate that her mom and dad had lied to her.

Two images of Clarence in 1941, in Defiance

* * *

February 14, 1943: “I made suggestion to Va. that we sell house and buy a 2-apt. in Chicago. Did she blow a fuse!”

March 8: “In eve. the subject of my chronic fatigue came up—and its concomitant—how it would be overcome by moving to Chicago. The result: one of those tense, tearful sessions which left me sleepless and exhausted.” Dad was becoming very tired living in a small town such as Defiance and having to board the train to go to Chicago to begin his two roundtrips for his mail runs before returning home on the train. Furthermore, at the height of the Second World War, because of rationing of such items as gasoline and tires, it was difficult financially to still own a car. (Production of automobiles had ceased during the war. I was not aware of that for several years.)

March 10: “Virginia conceded it might be best to move to Chicago or suburbs, but she didn’t like the idea of living in an apartment. We’ll almost have to sell the house, but it will be like selling part of ourselves.”

By July 1943 the house at 1129 Wayne Avenue was on the market and was sold by the end of the month. In early August, Mom and Dad took the train to Chicago, stayed at Fort Dearborn Hotel, and began searching for a house. They quickly found one that they bought for $10,500. (It is now worth $1.3 million.)

On the morning of August 16, the family packed up and moved from Defiance, Ohio, to Chicago. I couldn’t quite understand why my family was telling me to say goodbye to everyone in the neighborhood. I was only four, and I didn’t really realize what was happening. We were leaving the lovely two-story brick house that Dad had designed himself that was built the year before I was born.

We traveled in our Plymouth sedan to the big city and arrived there as it was getting dark. We spent the night at the Berkshire Hotel at 15 E. Ohio Street in what was then called Chicago’s Near North Side. The only thing I remember was all of us getting into a small compartment, a man closed the door, and when it opened the view was different. This was my first time on an elevator, and I couldn’t figure out what was happening. More recently the Berkshire has been remodeled as the whimsically named Acme Hotel, where I have stayed a couple of times. The bar is now known as the Berkshire.

The next morning we were back in our car and pulled up at 2118 W. Grace Street in the North Center neighborhood. The moving van soon arrived, and our furniture was taken into the first-floor apartment of the two-flat building. After Labor Day, Carolyn began sixth grade at Alexander Graham Bell Public School, some four streets up Grace Street. (Bell himself spoke to the students on the school’s opening day in 1917.)

I have been inside the Wayne Avenue house in Defiance twice since 1943. The first time was shortly after I moved back to town to become the college librarian, in 1968. The second time was in 2010, when my sister and I made a visit to Defiance. Carolyn had more memories of the house than I did and wished the owners had let us see the second floor. The then-owner was surprised to learn the house had been built in 1938. He said county records indicated it dated from about 1943. Carolyn subsequently was able to send him the date that our family moved into that house.

Settling into our new home and new city—not new for my father—Dad put the Plymouth on blocks and after another year or so, sold the car. When we were not walking, we were using public transportation. There were the red streetcars on Lincoln Avenue, the green ones on Irving Park Road and Western Avenue (before long to be replaced by trolley buses), and Chicago Motor Coaches on Addison Street. And there was the El, the series of elevated lines. We often took what was then called the Ravenswood Line and at the Belmont station transferred to the Howard Line, which then went underground in a subway that ran through downtown—otherwise known as the Loop—under State Street. That subway opened on October 17, 1943, and Dad rode it that first day on his way to work.

* * *

Now that he was back living in Chicago, Dad soon started attending the Sunday afternoon Forum meetings again after having missed so many during the years in Defiance. However, this was not without resistance from Mom. His diary shows him planning to go to one meeting, but because she complained, he stayed home that day. After that, however, he insisted on attending, and for the next several years he did, whether she liked it or not. Every once in a while Dad would try to give Mom a general idea of what the meetings were about, but she showed no interest. Rather than continuing to object, she eventually settled into resignation.

Upon moving to Chicago, Mom and Dad took separate bedrooms. I grew up during those years aware of occasional friction between my parents, but I really am unable to recall any specific episodes. Possibly I learned to dismiss them from my mind. For Carolyn, however, such friction seemed to affect her a lot, and years after both our parents were gone, my sister would comment that Mom and Dad’s arguments had considerable effect on our health, saying we missed school a lot because of all the tension. A cursory rereading of the diaries during my grade school years does show that I missed school frequently for other than the usual childhood illnesses—measles, chickenpox, mumps, German measles. Possibly I was just a sickly child. I know I was a finicky eater, and I was terribly skinny for years. Perhaps family tensions emotionally affected me in ways that I have largely forgotten. I do know that when a ringworm epidemic arose, I fell victim to that and was out of school for a few weeks. When I returned to school, I was very self-conscious about the stocking cap I had to wear for a while. I could tell it was difficult for some of my classmates to resist making fun of me. Still, I managed to remain being a good student and rarely fell behind in my schoolwork.

Initially we started attending a Methodist church that was just a couple of blocks away, but before long we began going to Ravenswood Presbyterian Church. The church has existed at 4300 N. Hermitage Avenue since 1907. This was slightly over one mile from our home on Grace Street. Usually we all walked the distance, but sometimes we would take the Irving Park streetcar for a few blocks, but that would still require a lot of walking to and from transportation. I remember Dad telling me that the main reason he chose that church was because its longtime minister, Dr. Clarence Wright, studied at McCormick Theological Seminary under Dr. William S. Sadler. (By the time the Urantia Book was published, we were no longer living in the city and attending that church, so I doubt that my parents ever mentioned the book to Dr. Wright.)

This church eventually became a spiritual home for all four of us. Both my parents, but especially Mom, began making friends with whom we all socialized outside of church. Carolyn readily took to the youth group called RIPS, which I think stood for Ravenswood Intermediate Presbyterian Society. Upon entering high school, she was involved with TUXIS. I have no idea what that stood for. I don’t really remember my early Sunday School years, but after a few years I recall discussing with Mom and Dad some of the teachings I was undergoing, primarily about the Old Testament. I sensed that neither of them believed in a punishing God. When I was old enough to take the church classes to study the catechism, I especially liked Dr. Wright telling us about Mark the gospel writer as a teenager fleeing naked from the Garden of Gethsemane when the temple guards came to arrest Jesus. That really made quite an impression on me! I myself enjoyed RIPS when I was old enough to join. I particularly remember us visiting the Baha’i Temple in Wilmette in I think spring 1953—I’m really getting ahead of the story—and being quite impressed with their belief that all religions worshipped the same God. I thought I might want to become a follower of that faith.

In 1944 I started kindergarten at Bell School, first in the afternoon during the first semester and then in the morning during the second term. By September 1945 both Carolyn and I were at Bell full time: she in eighth grade and I in first. I remember our teacher reading a little each day from L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz. I often joke since that when she was done, I was surprised I still had to continue going to school. Carolyn graduated from Bell the following June and was ready to attend Lake View High School in fall 1946. But that July she came down with polio. Dad was in Pittsburgh when he received a telegram from Mom saying Carolyn was in the Municipal Contagious Diseases Hospital at 3026 S. California Avenue. On August 1 Dad and I went to the hospital, but I had to remain outside on the entry porch and was unable to see my sister. I find it interesting that I was allowed to stay there unsupervised at the age of seven, and nothing happened to me. Later that day a nurse called to quarantine me and the premises against visitors. (This did not apply to our upstairs tenants.) When it was lifted about two weeks later, Dad says I exclaimed, “Hooray! I’m free! I’m out of jail!” While Carolyn was in the hospital, a girl in the bed next to her died. Carolyn was brought home on August 10, and Mom began using the Sister Kenny method of hot packs and muscle training exercises on her. Carolyn’s case was not serious enough to require prolonged immobilization. However, it did take weeks of care for her to regain her strength and to start walking again. She was prevented from starting high school that fall. It was early February before she started, and she experienced fatigue that first week or two, as well as a lack of confidence.

I like this little tidbit in Dad’s diary for November 19, 1946: “In aft. went to Bell School and had a talk with Miss Nemode, Larry’s teacher. She gave a good report of him, except that he was inclined to daydream quite a bit.” I was in second grade then. I remember Miss Nemode; she was rather attractive. She was still on the faculty when I graduated in 1953 and had long been married.

On October 26, 1947, Dad came home from a Forum meeting and brought Al and Charlotte Dyon and their daughter Jane. This was the first time I ever met any of them. Dad writes, “Very enjoyable visit. Jane was thrilled over Carolyn's artwork.” What I remember about the visit was Jane and I in my bedroom looking at cartoons I had drawn in about 1945 when I knew my alphabet but did not yet really know how to read. The balloons in the cartoons all had nonsensical words, and Jane and I both had a hilarious time laughing at them. It’s a shame these cartoons have been lost to posterity. Then on July 7, 1948, the two families got together again, this time at a woods in the west suburbs. (Memory serves me that it was Thatcher Woods. Dad does not give the name.) There was a friend of Jane’s named Judy along with us, and I remember enjoying her company even more.

The following December 6, Dad learned that Charlotte had died two days before. Before long, Jane was sent to live with relatives of her mother’s in Madison, Wisconsin. It would be several years before any of us saw her again.

I find it hard to believe that the two visits above were the only time I ever saw the Dyon family. For such a longtime friendship between Clarence and Albert, I wonder why we never got together much more often.

Along about 1947 or ’48 I joined Cub Scouts through a troop at the nearby Joyce Methodist Church. Actually, I was sort of forced to join. It was parents’ night, and Mom had gone along with me. Before I knew it, my friends had talked her into becoming a den mother. Obviously I now had no other choice but to join, myself. Mom then began having the den meetings in our basement. In reading her magazine for den mothers, I saw an article about a Cub Scout troop sponsoring a country fair, and I talked Mom into us doing that. Before long, one night in our basement the entire neighborhood seemed to congregate to see all the booths and other activities that were part of the event. I’m sure we were violating fire safety practices by having so many people in a rather small space that only had one entrance/exit. Still, as far as I was concerned, it was the highlight of my time in Cub Scouts. Later, when I aged into Boy Scouts, it was not so much fun, and I think I dropped out after two years, at the most.

In 1948 the Chicago Railroad Fair was held on the lakefront where the Century of Progress had been in 1933-34. This fair commemorated the arrival in Chicago in 1848 of train service to the city, which soon led to Chicago becoming a major transportation hub. Mom, Dad, and I attended it on August 13, and I had a great time seeing all the exhibits of numerous railroad companies, many which I had never heard of before. We rode the Deadwood Central narrow gauge railway that ran the length of the fairgrounds.

A particular highlight was the “Wheels-a-Rolling” pageant, which was an elaborate dramatic and musical presentation of several episodes in US railroad history, including a reenactment of the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory, Utah, in 1869 that celebrated the connection of two railroads coming together from east and west, thus creating the first transcontinental railroad system. We were seated at one end of the stands, and I enjoyed looking off to my left to see what trains were coming next. I had always been interested in railroads without ever having taken anything longer than a day trip between Chicago and Kentucky, such as shortly before, when Mom, Carolyn, and I visited relatives in Oldtown and environs. Because of his work with Railway Mail Service, Dad had a great love for and knowledge of railroads; and this fair instilled in me a similar attitude toward that form of transportation. I enjoyed the fair so much that I visited it one more time that year and then three times in 1949, when the fair was held over for a second year. One of those excursions was with Cub Scouts.

* * *

After seven years of being without a car and using public transportation, on June 29, 1950, Dad came home with a 1941 Pontiac sedan. Despite this car having its problems, the family managed to go on a trip to Oldtown and environs that August. The trip also included spending two nights with the Vandergriffs in Cincinnati and then a night with friends in Defiance.

Here’s something I don’t remember: On July 22 I went with Dad downtown to his train and “worked a few Indiana letters” on the mail car. I wonder if my father thought I would someday end up being a postal worker. As it was, I DID work part-time for the Post Office as a substitute mail carrier off and on during my college years, but I knew this was not going to be my career.

Carolyn graduated from Lake View High School on January 25, 1951, and threw a party in the basement of the Grace Street house that evening. Some of the attendees had too much to drink and started fighting. Before long, Carolyn got a full-time job as a receptionist for an advertising agency in the Wrigley Building by the Michigan Avenue Bridge.

Cousin Richard Womack, whose father Dick (Mom’s younger brother) had succeeded Grandfather Womack as postmaster of Oldtown a few years before, was now in the Air Force and was stationed at the now-defunct Chanute Base in Rantoul, Illinois. He started making weekend trips up to Chicago to visit our family. The first weekend of March 1951 he brought along an Air Force buddy from San Francisco named Jim Maldi. By April 8, Jim and Carolyn were engaged.

The next day, Carolyn began a new job at some kind of insurance conference office in the Loop. One of the employees she met that first day was a fellow named Tom Kendall. Carolyn immediately thought to herself, “I think I made a mistake.”