On Meeting Sister Crescence

In his own words, Mark Bloomfield tells of the day he met Sister Crescence and how he became instrumental in helping her establish the free schools.

MY LOVE OF ANIMALS was only eclipsed by my love for people on the one hand and my love for God the Father on the other.

My first trip to Calcutta—the scene of atrocious human suffering—was in 1987. After 11 more visits to India, in 1994 I decided to knock on Mother Teresa's door and work as a volunteer. My two main stints with Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity (MC) in Calcutta occurred between 1994 and 1995.

When she opened the door, the supervising nun welcomed me into the inner courtyard of the MC Mother House in the guts of Calcutta and assigned me to work the next morning in “Prem Dan,” the MC home for mentally ill destitutes in the Park Circus area of the city.

Several weeks later, I was moved across to “Kalighat,” an old converted Hindu temple in the southern suburbs, and Mother Teresa's original home for dying destitutes.

Working under a dear old MC sister named Dolores, I ended my first voluntary period a couple of months later as the MC undertaker, whose job it was in addition to nursing the nearly dead, to dispatch the actual dead to either the burning ghats or, if they were Christian, to shallow graves atop older graves in Tollygunge Cemetery.

Each morning, the normal pile of murdered female babies’ corpses also awaited burning, who had either been withheld food or whose spines were snapped at birth for not being male.

It was during my second period of voluntary work at Kalighat the following year that I started to notice that a number of patients were blinded by cataracts that a simple operation could have removed.

Obtaining permission from the MC sisters to escort the longer term patients who needed to have their cataracts removed to a local charitable eye hospital across from Prem Dan where I had worked earlier, I thus started the slow change of direction that later culminated in a number of free mass cataract surgeries for the destitutes out in various remote, rural parts of India.

For several years thereafter, what ever modest funds I could save in England as a result of my own labour, I would bring to India and lay on another free “eye camp” in conjunction with local Indian eye surgeons culminating in another two or three hundred deliverances from the curse of curable blindness.

But it was while sitting in a corridor of the Calcutta eye hospital with one of the female MC patients whom I had escorted there for treatment that I struck up a conversation with a kindly-looking, nearly-blind Indian nun sitting next to me who was also waiting for a doctor.

Her name was Sister Crescence and the rest, as they say, is history.

* * *

Crescence and I really got on well together that afternoon. We were not only kindred spirits, but she spoke near-perfect English. Though suffering from an incurable eye condition, she still ran her convent school up in the notoriously dangerous and backward northern Indian state of Bihar each day as though she were in perfect health. Before we parted company we agreed that I should visit her up there and continue the conversation about new and creative ways to serve the disadvantaged.

Upon my arrival at St. Mary's Convent School in Motihari, Bihar, [FOOTNOTE: Where Sr. Crescence was then Mother Superior] some weeks later, Crescence wasted no time in telling me what was on her mind. Each afternoon at her little boarding school on the edge of town the classrooms would stand empty after the day's classes whilst the most impoverished children living with their parents in tiny mud huts in the area would receive no education at all as their parents couldn't afford even the modest

convent school fees.

Crescence wanted to win such impoverished parents over to the idea of allowing just one willing daughter of each family to attend a free school each afternoon after the normal school had finished when the classrooms would otherwise be empty.

She went on to elaborate how the girls should be prioritized as not only were they rarely put through a full education and often would receive no education at all, but in later life when each might become a mother, whatever they will have learnt at school would automatically be imparted to their children. Only one child from each family should be encouraged to attend but with instructions to teach all she learns each day to her sisters

and brothers.

A special concentrated syllabus of reading, writing, arithmetic, hygiene, useful crafts and income-generating skills such as sewing as well as civics lessons would be taught but with time also for some fun and games to give them a chance just to be kids and not child laborers as is their normal lot.

Retired, respected female ex-schoolteachers, themselves in desperate need of an income would be asked to run the classes in return for a fair and decent salary. All study materials as well as the lessons themselves would be free of cost to such children in addition to which, one small nutritious snack would also be given each day without cost.

The only thing that was stopping Crescence and her few fellow nuns from making it happen was their lack of funds to cover the salary of the first teacher they needed to bring in, plus what little else they needed for books, pencils, etc.

Emptying all my rupees I happened to have stashed on me at the time on to the table, I said, “Do it!”

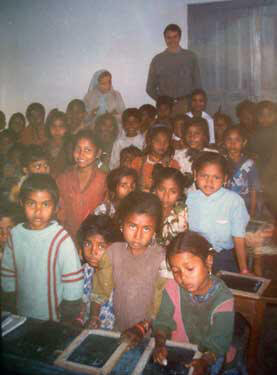

From that time onwards, the receipts, the thank you letters, the photos have kept coming. Whenever I'm in India and can make it over for a brief visit, the sight of the kids, (anywhere up to a hundred of them) is enough to make me weep with joy.

Typically, when I visit them for ten minutes or so when they are in class they sing me a song that they all mime to and end up giving me a big cheer. Once they put a medal around my neck that they had handmade from cardboard.

The last time I dropped in for a visit they were having their annual sports day, taking a break from normal classes just to have a good laugh together. That was the time Crescence took me aside asking to speak about a money issue. Thinking she needed more, I was about to ask how much; instead, she said she was given twice what she actually needed last time, and could she give me the rest back? That one naturally brought a chuckle. We did the math, and it worked out she was putting each girl through a whole year of life-changing education for US$3—a full year of education for the

price of a hamburger.

A small clutch of close friends have also kindly donated small sums over the years to help upkeep the two schools now, and each receives their own letters, receipts and photos from Crescence herself, who still insists on writing even though she can hardly see the notepaper. One Australian friend by the name of Robert Coenraads even managed to visit the school with me a few years back and who had to fight back the tears of joy that such a sight stirred in him. Needless to say, Robert is our most ardent supporter now and is already talking of pairing up Indian and Australian schools along the lines of the same model.

There are a million villages in India alone and the freeschool model may be replicated an unlimited number of times wherever there is poverty, discrimination, misery and despair. The freeschool model might not offer a solid guarantee that each child will go on to rise to their full potential from the dark abyss of the cycle of ignorance, but it at least gives them a fighting chance where previously there was none.

Life from death? No. But light from darkness? Hope from hopelessness?

Mark Bloomfield (2004)